Alanbrooke and the Kearton Brothers

One thing leads to another. Recently I got round to reading a copy of Alanbrooke’s War Diaries I bought in March, a thick tome. General Alan Brooke (who combined his names into the title Alanbrooke following being ennobled after the war) was commander of the UK Home Forces, 1940-41, then Chief of the Imperial General Staff until the end of the war. A very important, but lesser-known figure from World War Two, he was head of the British Army, and the Empire’s senior soldier, working closely, but not always harmoniously with Churchill.

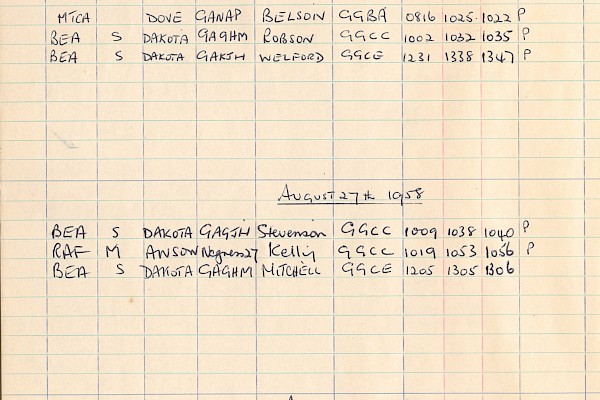

In the Archives, we’re in the habit of checking book indexes for “Shetland.” Alanbrooke did turn up, with visiting Orkney and Shetland on the 14-15 May 1941, and spending a night here. Military diaries and memoirs aren’t always complimentary to Shetland, but Alanbrooke was certainly happy some of the time. He made a trip out to Noss – wonderful 600 ft cliff covered with gannets, guillemots, kittiwakes and a few cormorants. Alanbrooke was a bird watcher, and the diaries refer to his attempts to photograph and film them. Lerwick Town Clerk George W. Russell was with him – a great bird authority and had worked with the Kearton brothers in the old days.

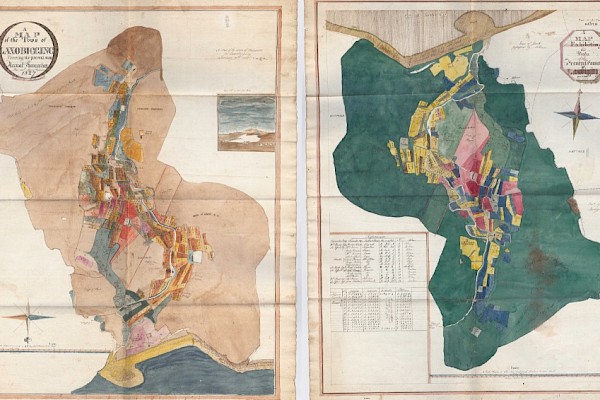

Who were the Kearton brothers? There’s six references to the Keartons in the archive catalogue, and some emails to knowledgeable people like Jonathan Wills and John Ballantyne helped more. Richard Kearton (1862-1928) and Cherry Kearton (1871-1940) came from a farming background in Yorkshire, and were pioneer wildlife photographers. They seem to have been in Shetland twice, in summer 1898 and again in 1913. Most of the photographs seem to have been taken by Cherry, while Richard wrote books, and did magic lantern lectures.

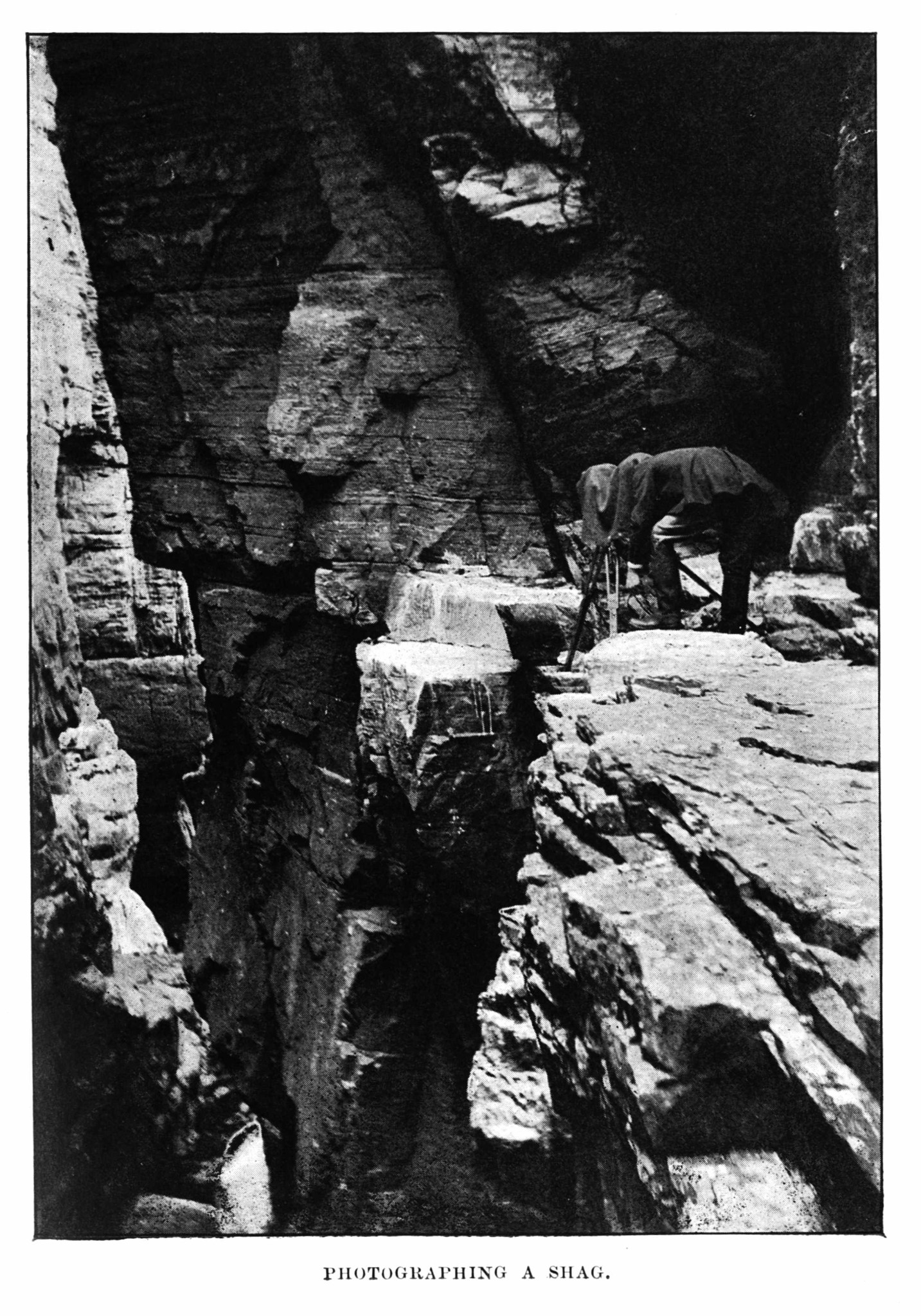

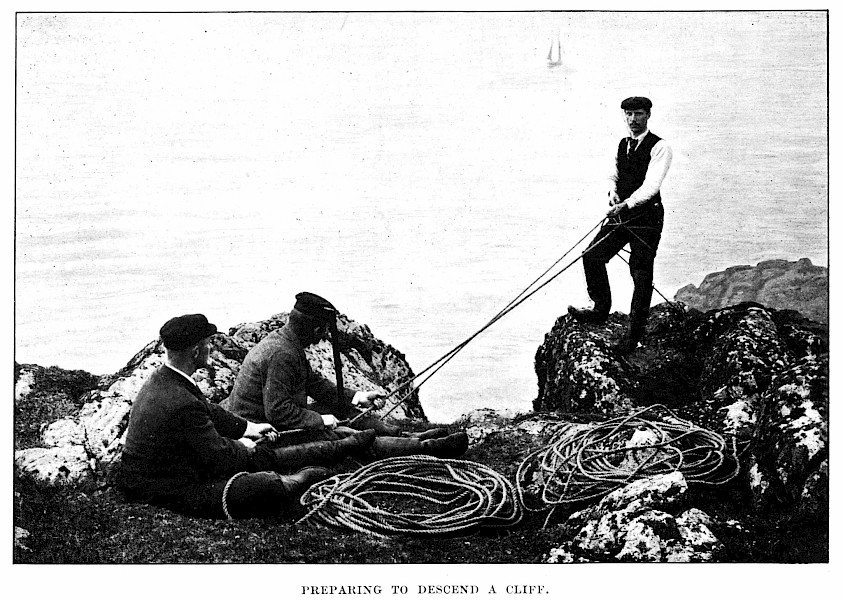

We have one Richard Kearton book – Wildlife at Home. Fortunately, it deals with their 1898 adventures in Shetland. The Keartons used a half-plate camera, with a special Dallmeyer lens, and a silent Thornton-Pickard shutter. Good at the time, but heavy and highly visible, and they needed to get close to the birds. They constructed ingenious hides, including a dummy ox, but part of the book is about the right and wrong ways to lower a photographer over a cliff. Use two good manilla hemp ropes and drive a fairly stout crowbar eight to twelve inches … into the ground. There were opportunities in Shetland, and there’s a photograph of Cherry being lowered down with the aid of Dr Saxby and the Unst laird Laurence Edmondston, probably at Hermaness.

Cherry had a narrow escape trying to photograph a sea-eagle’s nest when his rope loosened a stone. He dodged it,but got a glancing blow on his left thigh. The nest was deserted anyway. There’s a photograph of Cherry in Shetland, standing on a cliff ledge, camera on a tripod, black sheet over his head, concentrating on a shag. He must have had nerves of steel, and a bit more (see below for image).

Like Alanbrooke, the Keartons were impressed by Noss – the famous Noup of Noss, which is a perfect sea-fowl paradise. Always alive to opportunities, on a couple of poor days, they stayed in their room in the Queens Hotel and photographed gulls from the windows. Their trip to Hermaness led to a short piece on the bonxie – terrific downward rushes from an altitude of about two hundred feet. They approvingly noted Laurence Edmondston’s conservation efforts, and how the bonxie breeding pairs had doubled.

The Keartons were part of how the study of birds modernised, moving away from shooting and stuffing. Photography was a new way of collecting evidence – their images proved sparrowhawks built their own nests. Equipment has revolutionised since 1898, and images have become so much easier to get. Nowadays, the brothers’ efforts look old-fashioned, but their knowledge of lighting, technique and skill must have been truly considerable, not to mention determination and pluck.

But back to Alanbrooke. If he’d been a much younger and less important soldier he might have been stationed in Shetland. He’d have been able to spot birds on moorland route marches. He’d have got to know the banks and seen the solans, maalies and bonxies. He’d have rejoiced in the whaups and the shalders, and many, many more.