Captain Lawrence Irvine

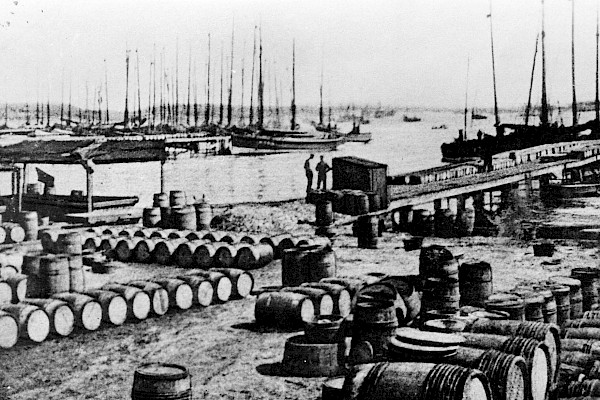

Captain Lawrence Irvine of Bridge of Walls was one of the few Shetlanders to enter the West Indies Trade in the late 1700’s, a trade based on the slave economy. Delving into the archives we learn more of his life, the portrayal of his achievements, and the Shetland connection to the systematic cruelty that stretched across continents, oceans, and generations.

On the sixteenth of August 1777 a Shetland sailor made his will. Lawrence Irvine had left the sea and established himself as a wine merchant in London. He’d done well for himself, well enough to offer five hundred pounds each to his youngest sons. Further down the document, among the neat but sometimes difficult chancery script there’s a reference to a “gold watch gold medal and a silver cup.” The cup is important. One wonders, did Lawrence think back to his life of adventure when those words were written.

It isn’t entirely clear when Lawrence Irvine was born - he died in 1778 - but it was in Shetland, Bridge of Walls, son to a John Irvine. He retained some sort of legendary status among Shetlanders for a time. Enough for the antiquarian Gilbert Goudie to make a note about him. The source was Lawrence’ distant relative Duncan Irvine, then holder of cup, in Edinburgh.

We’re lucky that Gilbert Goudie bothered, for his note fills in details the will doesn’t offer up. Lawrence started making a living in the West India trade. A brother, Duncan, seems to have established himself south earlier. The Irvines may have had enough resources or contacts to place Lawrence in a ship. He made himself useful. Gilbert Goudie says he was able to take command of a ship when almost all the crew were lost. A grateful underwriter awarded him a gold medal.

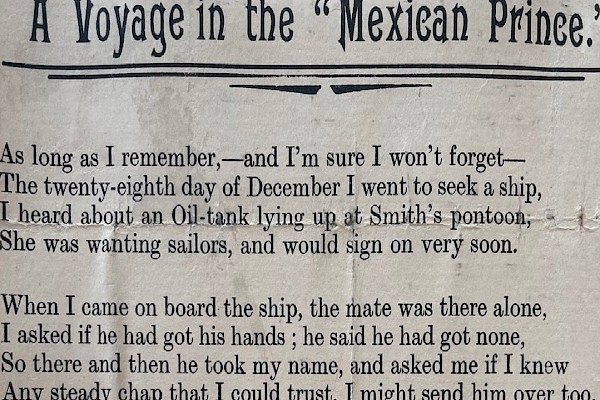

The West Indies trade was inherently dangerous, as seafaring invariably was in those days. A few Shetlanders found positions in it. Captain Bruce, who came from the defunct Breiwick branch of the Shetland Bruces was another one. It was a lucrative trade, the slave economy products of sugar, rum, coffee, and some lesser known ones like indigo, made money, lots of money. Lawrence Irvine was brave, resourceful, and not at all afraid of a fight. It was just as well, as the frequent European wars made prey of the civilian ships. In 1758 he was captain of the Lyon.

Whitehall Evening Post or London Intelligencer, August 8 - August 10, 1758

The underwriters, grateful once more, rewarded Captain Irvine with a cup. It seems to have had an adventure when it was stolen in 1763, but was back in the captain’s possession when he made his will. Lawrence Irvine was on his way. He married up, to Lydia Catherine Chamberlayne, of Maugersbury, Gloucestershire, the sister of Admiral Charles Chamberlayne. According to Gilbert Goudie, there was a portrait of the couple, allegedly by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Lawrence Irvine also acquired a literary connection, as the Chamberlaynes were relatives of Jane Austen. After Lawrence Irvine’s death, his widow moved to Bath. She gets a fleeting mention in one of Austen’s letters.

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, 2012. The cup is 340 x 300 x 180 mm, and is the earliest the museum possesses. The inscription reads – “To CAPT. LAWRENCE IRVINE, this Cup is presented by the Underwriters, in gratefull [sic] Commemoration of his bravely Beating off a large French Privateer wch boarded his ship the Lyon in Auracabessa Harbour in Jamaica on April 12th 1758.”

All that remains of Lawrence Irvine’s various awards is the cup. The National Maritime Museum hold it, and a few years back it was on display. Certainly, it represents Lawrence Irvine’s capacity for valour, it also represents a trade rooted in utter brutality and control maintained by the extravagant use of violence. Captain Irvine would have known this and seen it. We don’t know what he thought about it, or how he justified it. It allowed him to advance in society, and unlike many white men in the West Indies of the time, his advance was at considerable risk to himself. For most people who saw the cup, then, and years afterwards, it represented heroism. In our own time, like so many things in Britain, seen and unseen, it also represents a connection with systematic cruelty that stretched across continents, oceans, and generations.

The Shetland Museum and Archives is committed to safeguarding and promoting all of Shetland's heritage ensuring it is accessible and enjoyed by all.

Find out more about our commitment to equality, diversity and inclusion in all that we do.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.