Christmas in Shetland - 1923

1923, like many of the years between the wars, was not a good one. The Shetland Times year end report spoke of a poor herring fishing, and boats barely clearing expenses. White fishing was a little better, and on the land the potato crop failed. There was a healthy demand for Shetland woollen goods, and still a demand for the new product – the jumper. So how was Christmas in 1923?

It was a white Christmas, with sledging, or “sleighing” as the Shetland Times put it. Gullets Brae, it said, was a “favourite resort” on Christmas Day. There hadn’t been enough snow “for free and unlicensed tobogganing” for some years. Helpfully, the Town Council had declared that day a public holiday, and fun was had outside.

The Post Office had dealt with over 3500 parcels over the weekend preceding Christmas, and on Christmas Eve sent 1100 telegrams. They employed ten ex-servicemen to help out. The Great War still was recent, and the announcement of the War Memorial unveiling was nearby in the newspapers. Deliveries had gone ahead despite snow blocked roads. The mail steamers had been delayed by bad weather – in some ways 1923 and 2023 aren’t that different.

Church services were highly important at this time, and often elaborate. St Ringans United Free Church held a carol service, with string instruments as well as an organ, featuring a cello solo. Miss M. Shearer sang “A Dream of Christmas,” and her “exquisite voice brought out its quaint haunting charm.” The St Ringans service was scheduled for a repeat on 30 December.

The Lerwick Parish Church, or “da Muckle Kirk,” held a service on the Sunday preceding Christmas, given by Sunday School children. The Shetland Times listed the soloists, and another service followed on Christmas Day.

Peerie guizers came out on Christmas Eve, reported as being in smaller numbers than usual – but it had been snowing. Older guizers came out later, with the paper saying “ladies exceedingly well represented.” Some houses opened for the guizers, and the Rechabite Hall too. There were so many there that the crowd got in the way of the dancing.

The inmates of the County Homes, aka the Poorhouse, or the Brevik, got entertained on Christmas Eve, a bright spot in a spartan regime. Miss M. Shearer, who was having a busy festive season, entertained. Mrs Yule of Ordgarff handed out gifts with “a smile and a cheery word for each inmate.”

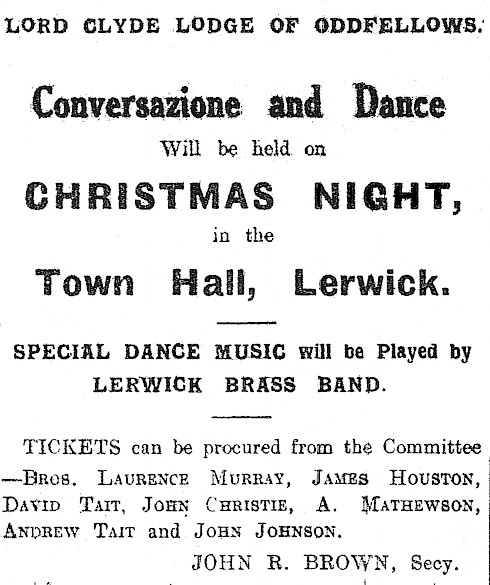

The Oddfellows, like the Rechabites a temperance organisation, put on a “Conversazione and Dance.” A Conversazione – a word not used nowadays – is a scholarly gathering for discussion of art, science, and literature. Most people were there for the dance, no doubt, although the Times reported an “excellent tea,” as befitted a teetotal body. Miss M. Shearer was there too, and music for dancing came from Gideon Stove, violin, Mrs Moffat, piano. The Lerwick Brass Band also played for some of dances.

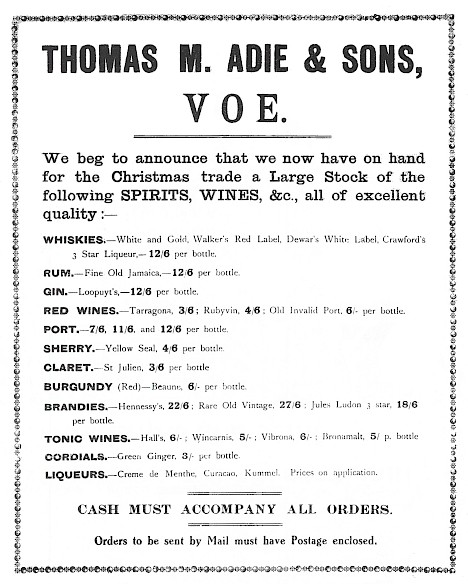

A word about temperance. Lerwick, and some other Shetland parishes had voted themselves dry – that is, difficult to buy alcohol in, and no public houses. So some people’s ideas of a celebration were curbed, and the temperance organisations were important venues. In any case, drink was expensive. You could get it mail order if need be, as T.M. Adie in Voe pointed out.

News of celebrations in the country filtered into the New Year newspaper issues. Gutcher school had a do on on 21 December. Guizers – “four strangely dressed individuals” – representing the universities of Japan, Egypt, Glasgow, and Australia, came in on “an educational tour through the Shetlands,” and were able to join in a Shetland reel. Levenwick school also held a pre-Christmas concert and dance. Fiddlers were “Messrs Youngclause, B.H. Colvin, and J. Johnson.” Youngclause was most likely Jock Youngclause from the Ness, aged about thirty-eight, the noted Ness fiddler. B.H. Colvin was boy about fourteen, and James Johnson, forty-six – your writer’s uncle and grandfather. Dancing “continued with zest until early morning.”

1923 was deep in the era when Christmas presents were modest, and that year’s economy wouldn’t have made them less so. Working class people who were children between the wars spoke of being grateful for an apple or an orange in their sock. More middle-class children in the villa zone between Lerwick’s Hillhead and the Burgh Road would have got what we think of as presents now. Celebrations were very local affairs where people came from near, not far, to friendly social events. Later on in January 1924, Shetlanders, who had long been fond of the Julian calendar, still held a few events on Old Christmas and Old New Year.