Our new photographic exhibition ‘Men in Tights’ focuses on Up Helly Aa squads from 1905 – 1923 which made use of a favourite UHA disguise – men dressed up as women.

Our new photographic exhibition ‘Men in Tights’ focuses on Up Helly Aa squads from 1905 – 1923 which made use of a favourite UHA disguise – men dressed up as women. Here curator Dr Ian Tait tells us more about how the display came together, the photographer behind the images and the fascinating themes that inspired the costumes and capture a moment in time.

What was the inspiration behind the ‘Men in Tights’ exhibition?

There’s nothing unusual in many guizers modelling women’s clothes any more than the male, animal, or inanimate creations of a century ago. What interested me was the much more impressive creativity of the early outfits, borne of everything being laboriously hand-made, and of equal fascination were the ideas behind the themes. Looking back, we can see local and outside topics, political and whimsical, factual and fictional. Some plain inexplicable, such as the unlikely “Schoolgirls of the Sixteenth Century”, and such nonsense appeals to me!

Why did so many of the squads past and present dress up as women?

Up Helly Aa is a festival of fancy dress, and the guizers in the procession wear costumes of all kinds, from elaborate to pretty basic. The common theme is disguise. From the earliest days many of the guizers, or often whole squads of them, have disguised themselves as women. For men wanting to don comic disguise, wearing female attire was an obvious choice, from comedic effect and women's clothes were brighter and more attractive than male costume of the time. The guizers didn’t try to mimic female physique, but just went into disguise. Guizers had plenty of female subjects to model, and some squads went out on political topics, but most were more whimsical, such as the “Merry Milkmaids” of 1921, and historical themes were always popular like “Grace Darling” in 1910.

It’s interesting that many of the costumes seem to have a political or topical theme to them. What were the main sources of inspiration in the early 20th century and how was this reflected in their choice of costume?

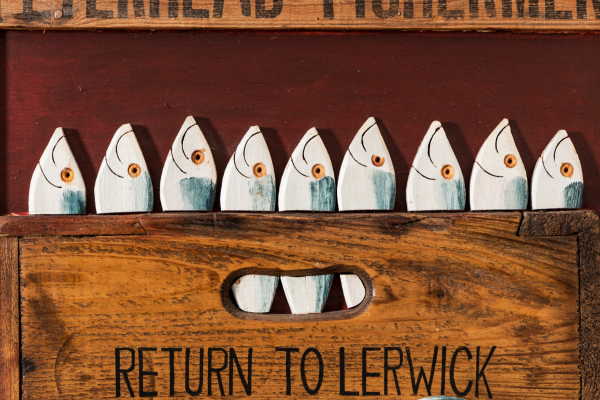

Some of the topics were inspired by the local scene, like “Dutch Vrouws” of 1906, which recalled the prevalent Netherlands herring fishery. The 1909 squad “Suffragettes” featured voting campaigners, complete with a banner reading “VOTES FOR WE-MEN”, playing on Shetland dialect. A squad two years later was “Who’d be Toffs?”, bringing to mind the aristocracy then under pressure from parliamentary reform.

What are the key ways that you think the event has changed in terms of themes and costumes over the years?

A constant is the local commentary aspect, but culture beyond Shetland has usually predominated. In the early days, all ideas were still untried, so squads tried-out national dress of folklore; these subjects like “Tyrolese Girls” might seem a bit tame today. Commentary on politics – local or national – has always featured, and this has rather increased. There’s a more comedic vulgarity today that’s absent from the early squads: 1908’s “Gilbert Bain Hospital Nurses” look like the real thing (except for the moustaches!), but guizer nurses today are likely to have false boobs and fishnet stockings.

Can you tell us more about how the costumes were made-up?

Compared to today, a huge amount of effort went in. In the days before instantaneous visual media, those men weren’t short for ideas. Having chosen the topic, and how to represent it, work began on making the outfit and props. Of course, a fair bit of that goes on today, but a century ago everything was hand-made. Garments were cut-out and sewn (often by the guizers’ womenfolk), elaborate heads were made from papier mache and rope, and props were painted, soldered, and riveted. No customised costumes bought online for those chaps!

Tell us a little about the photographer whose work is in your show and who were the photos for?

They’re all the work of one of the finest local portrait photographers, Robert Ramsay. He set-up his his photographic business in Charlotte Street in the 1890s, when he was only in his twenties. He started off in landscapes and topical subjects, but later specialised in portraits. Most Up Helly Aa squads in the 1900s-20s went to him for their costume photograph.The squads got a set of two – “masks on”, and “masks off” – and the guizers ordered copies which came as postcards which could be posted to friends.

Are there any particular stand-outs for you in the exhibition?

At danger of sounding po-faced, I’m very impressed with the intellect behind many of the squad themes. For example, 1905’s “Bluebeard and his Wives” enacted an old French fairytale, where the character had several wives, who all disappeared mysteriously. Nuns today would be ripe for lurid parody, but a 1912 squad went so far as to model a specific Irish Catholic order, the Sisters of Mercy. My favourite has to be a 1908 group who went out as shepherdesses. No Little Bo Peep outfits for them: they went out as 18th century Saxon ceramic ornaments, in the squad Dresden Shepherdesses! The costumes are wonderfully elaborate, just like the ornaments they modelled.

The other noteworthy thing is that we can see the very beginnings of popular culture impinging on the scene, such as 1907’s “Whole Dam Family at Up Helly Aa” (emulating an American cartoon series), and a 1913 squad modelling two music hall comedians – the equivalent of television comics today. This is what begat the rather flimsy format of modelling television programmes and personalities today; all the characters are ready-made.

From what started as a pretty informal affair with only 300 or so guizers to now well over 1,000, UHA has grown hugely in popularity. How do you think it is relevant today and why does it appeal?

For the participants, it’s all about the moment: the spree of going out and about on a night of revels with your friends. The same goes for the hosts in the halls, although in the early days it was more of a homely affair, with guizers going between houses. That informal aspect is gone forever, as the town and the festival have grown hugely, and the event (although still by and for the local clientele) is now massively impinged on by the media. The guizers of the 1910s would be flabbergasted to see their modern equivalents paraded on the mainland and overseas throughout the year. The suspension of normality for the night continues, where people of all walks mix together in a way they mightn’t usually so readily.

‘Men in Tights’ is on display in Da Gadderie until 22 February.