James A Teit: Tackling racism in the late 1800's

In December 1883, Lerwick Man James Teit emigrated to Canada where he lived and worked with indigenous communities, listening and learning about their rich culture. His wonderful investigations into the lore of indigenous societies, and his political struggles alongside oppressed people, were models of anti-racist practice.

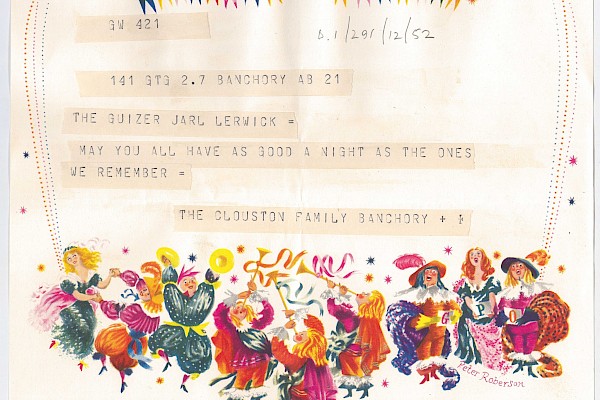

In August 1850 a young woman from Gulberwick emigrated to Australia. She took advantage of a scheme whereby Shetland women got assisted passages. We get “as much meat as we can look at”, she wrote complacently to her mother.

“We can go on deck”, she continued. “For my part I think I shall not care for going as there is a blackfellow of a sailor whose appearance is by no means – delightful.” Elizabeth Tait must have missed some striking views on the voyage out because of her casual racism.

In December 1883 another Shetland Tait left home. James Alexander Tait, who eventually changed the spelling of his surname (he was an enthusiast for everything Norse), emigrated to Spence’s Bridge in British Columbia. He went there to work in his uncle’s store.

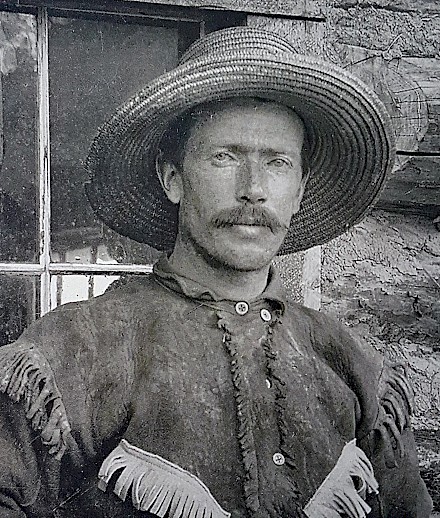

James Alexander Teit

Native people frequented the shop, and James Teit grew to like them. He didn’t have a racist bone in his hefty body, unlike many of his neighbours. He listened to the indigenous people and studied their rich culture. Eventually he married one of them, Lucy Antko, and established a ranch with her in the Twaal valley, next to her old home.

His good news caused consternation in Lerwick. His father wrote to remind him that he could never take his bride home. “She would naturally find herself out of place”, John Tait burbled. In Canada James found himself described as a “squaw man” or a “siwash man” (from French sauvage), by dolts.

It didn’t bother him. He had the capacity to treat prejudice with contempt, and to relax in his own environment. Every now and again he headed into the solitude of the interior to hunt.

At home he learned his wife’s language and listened to her accounts of indigenous lore. He began to make notes, sheaves of them. The anthropologist Franz Boas met him, and signed him up as a research assistant, a relationship which lasted for the rest of Teit’s life.

In due course James began to play a major part in the campaign against racism in Canada and the northern USA. It was an extraordinary and admirable step for the Lerwick boy to take. But first it is worth looking at his scholarly work.

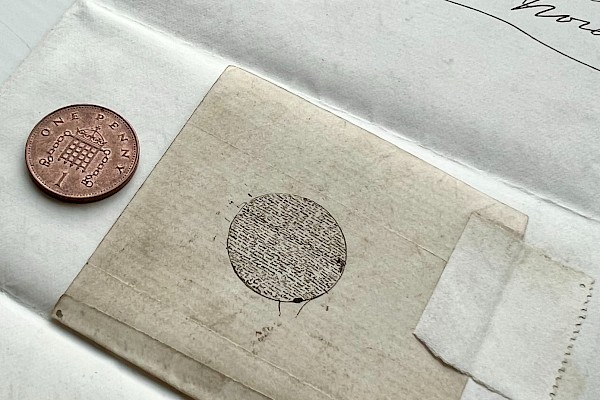

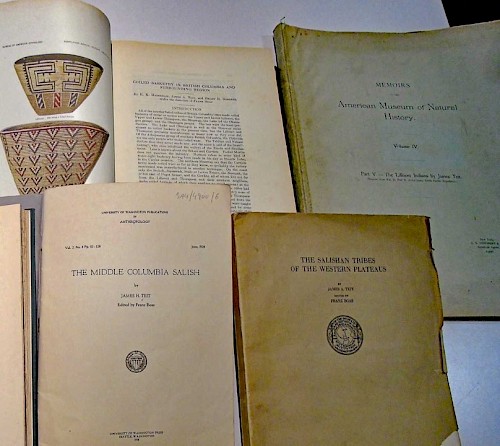

In all he published more than 2,000 pages of material about indigenous peoples. He sent copies of his monographs home to his friend Sandy Ratter, to place in the Lerwick reading room. (These texts are now in the Shetland Archives.)

Some of James A Teit's Writings, held in the Shetland Archives

A very good way of sampling the material he collected and expounded is to look at Judy Thompson’s big book Recording their Story: James Teit and the Tahltan, published by the Canadian Museum of Civilization in 2007. It is chock-full of information that he collected and photographs that he took, of native crafts: mooseskin moccasins, mittens of caribou skin, children’s winter shirts.

He gathered material about the people’s tales and beliefs. He was a careful researcher. “I am taking great pains to get hold of the true way,” he wrote to a colleague in 1912, “and have asked a number of informants. So far they all agree so I feel confident I am correct.”

(By the way, he devoted time to Shetland traditions as well, and kept in touch with other Shetland immigrants. In 1918 his article about “Water-beings in Shetland folk-lore, as remembered by Shetlanders in British Columbia”, appeared in the Journal of American Folklore.)

In her recent biography of James, At the Bridge (2019), Wendy Wickwire has given us a fine account of his scholarly methods. “Nothing in his ethnographic writings or his political writings”, she says , “suggests ‘salvage for salvage’s sake’, or anthropology as an act of ‘speaking for’ or ‘about’ naïve peoples lacking the capacity to speak for themselves. His was never a friendship forged to extract knowledge for abstract analysis. Teit pursued knowledge in the service of the community …” James’s work was the opposite of a racist anthropology.

Antko died in March 1899. “As she was a good wife to me”, James wrote to Boas, “and we had lived happily together for over twelve years, I naturally took her demise as a great blow.” He married again, and continued his anthropological work. Eventually, however, he devoted the second half of his Canadian career to activism as much as to scholarship. I have a feeling that that new departure in his life was partly a tribute to Antko.

As time passed, then, his interests turned more and more to the social and political troubles of his Indian friends. When he interviewed them about ethnographic matters, the discussion turned more and more to the ways in which they were oppressed.

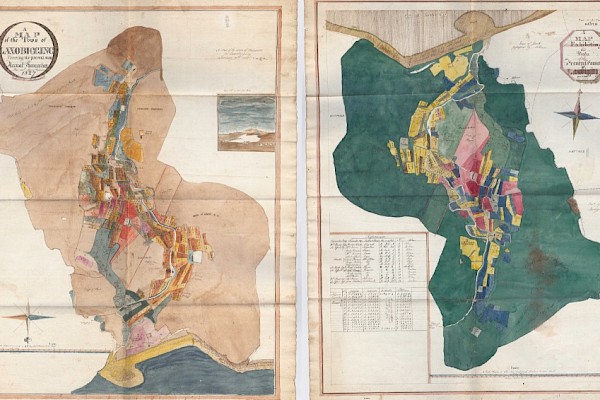

In 1876 an act of parliament had reduced the Indian population to “a distinct legal category”. They were treated as minors without rights of citizenship, and their affairs were dealt with by apparatchiks called “Indian agents”. Ten years later the Supreme Court of Canada deprived them of legal rights to their land.

When they called on their friend James to be their helpmate, he couldn’t say no. There was “no resisting the Indian appeal”, he said. “I was so well known to the Interior tribes and had so much of their confidence, and was so well acquainted with their customs, ideas, languages, and their conditions and necessities.”

Since 1901, when he had made his only return visit to Lerwick, James had taken an interest in politics. After discussions with Haldane Burgess and other friends at home he became an adherent of social democracy. He made contacts with the Socialist Party of Canada. Those political views fed into his activism. But after 1910 the activism came first. It was “the beginning of a worklife of unfathomable complexity and commitment”, according to Wendy Wickwire.

One of the important ways in which he helped his friends was to act as a translator. His linguistic skills were marvellous. Someone recalled hearing him translate for his Indian colleagues at a public meeting, “in clear, cultured English”. The observer was struck by the “simplicity, felicity, and clearness” of James’s renderings from difficult languages. It was as if “every sentence was ready for the press”.

He wrote documents for his friends as well, and helped them with their lobbying. He negotiated alongside them with the prime minister. In 1912 he convened a meeting of chiefs – about 450 of them! - at Spences Bridge.

As Boas said, in an obituary of James, “[u]nceasingly he labored for [the Indians’] welfare and subordinated all other interests, scientific as well as personal, to this work, which he came to consider the most important task of his life.”

When war came the government thought that it would be a good idea to conscript Indians. James exploded. “The War”, he said, “is a disgrace for people calling themselves Christian and civilised. All these nations claim to be fighting for democracy. This is quite ridiculous. Who ever heard of any modern capitalist class fighting for democracy?” And a few weeks later: “I am quite disgusted. I believe socialism alone is the cure.”

James Teit became seriously ill in 1921. His Shetland friend Sam Anderson was in Vancouver when James was there for treatment. “When I went up to say goodbye to him”, Sam said later, “the day before I left Vancouver … I was amazed at the sight. All around the hotel … on the pavement were Indians sitting crouched with their backs against the building patiently waiting for news of their best friend.”

He died nearly a century ago. There is still plenty of racism in the world. The Gulberwick woman who refused to look at a “blackman” is still typical, or perhaps not untypical, in some communities. Blacking up and bigoted abuse still go on, a matter of entertainment to the foolish. Here and there a police officer thinks that it’s important to stop and search black people routinely, or kneel on their throats.

James wasn’t afflicted with any of these incapacities. Was his scholarship and activism, then, a waste of energy? Of course not. Every argument and campaign against racism is worthwhile. James Teit’s wonderful investigations into the lore of indigenous societies, and his political struggles alongside oppressed people, were models of anti-racist practice.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.