Northwest Passage

On the 26th of June 1576, three ships anchored near St Ninian’s Isle. These were the Gabriel, a twenty-five tonne barque, the Michael, and a small scouting ship. The ships had left London almost three weeks earlier, setting off their cannons as they sailed along the Thames. The racket was heard by Queen Elizabeth, who came to her window and gave the ships a wave. The voyage was of great national importance and she wanted to wish the sailors well.

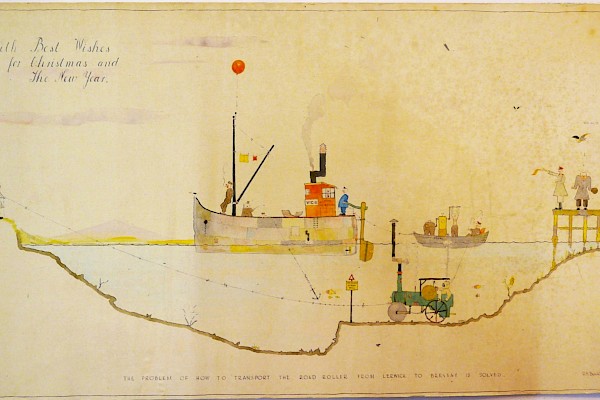

The vessels had been in Fair Isle two days earlier, sheltering from a gale. When things improved, they set off, only to find that the Michael had sprung a leak. They made for St Ninians (or the Bay of St Tronians, as the expedition’s leader, Martin Frobisher, called it), where they fixed the leak and took on fresh water. Then they got going again, sailing into the north Atlantic as fast as the wind would take them. At the time, most of what lay to the north-west of Shetland was vague and mysterious. Even the most up-to-date charts, which Frobisher had on board, might have warned Here Be Dragons for the area the sailors were heading into. What were the ships doing there? What were they trying to find?

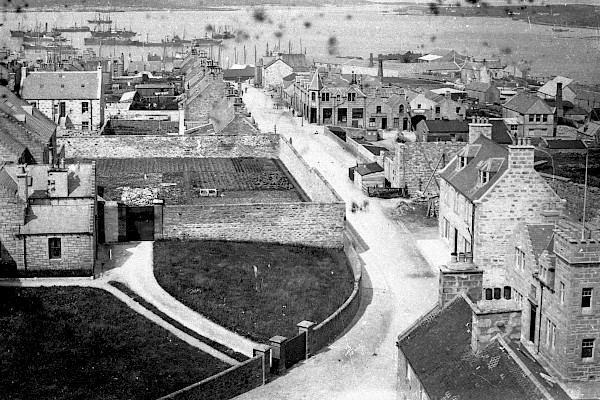

A highly decorative map of Shetland from the 1620s. Photo © Shetland Museum and Archives Online Library, image ref 01264

This was a time of enormous colonial expansion for European states. Catholic nations like Portugal and Spain had established substantial, profitable colonies in the Americas and, not to be outdone, Protestant England wanted to get in on the action. England had valuable trade routes to Russia, but, as is the way with colonisers, they were always on the lookout for more. One way of increasing the greatness of their empire would be to find a sea route to China, or Cathay as it was called at the time. If they could discover a way to get ships there and back with relative ease, their buccaneering seamen could unlock the riches of the east. That’s what the sailors were up to. They were searching for the fabled northwest passage.

The idea of the northwest passage had been speculated on by intellectuals since the late 1560s. In a book exploring the idea, the author, Humphrey Gilbert, wondered if the American continent was, in fact, Atlantis, and, if it was the lost island, whether it would be possible to sail around the top of it until you ran into China. This is the theory that Martin Frobisher and his comrades were testing when they set sail from St Ninians Isle.

Gilbert’s book had a dedication to ‘a great learned man’, and it is to this same man that Frobisher wrote while his leaky boat was being fixed. This was Dr John Dee, a scientist and philosopher who, in the weeks before the voyage, had schooled the sailors in the latest cartographic and navigational techniques. Dee, who Queen Elizabeth called ‘my philosopher’, had studied in Europe and was a pioneer in the use of mathematics and geometry for sailors. He also owned the latest maps and the most advanced navigational instruments that existed at the time. Adventuring sea-dogs like Frobisher may have been suspicious of this intellectual, land-lubberly approach but, as they made their way to Shetland, he put what Dee had taught him into practice. In a letter Frobisher wrote to ‘the worshipful and our good friend M. Dee’, he reports a latitude measurement he made somewhere off Sumburgh Head, using an instrument called a cross-staff, the first such measurement he had made in open sea during the voyage. The procedure involved standing on the pitching deck of the ship, holding up the cross-staff, and trying to gauge the angle between the horizon and the mid-day sun. It couldn’t have been easy, but the position Frobisher recorded was accurate to within a few nautical miles. Despite not being a sailor, Dee knew what he was talking about.

Frobisher continued to utilise Dee’s knowledge as they sailed further north. But, even with the latest thinking and ideas on board, the sailors didn’t find the northwest passage. They had a rough time with ice, Arctic fog, storms and understandably hostile natives (they marooned a man, who acted as a pilot, on a rock instead of returning him to his village). Eventually, on 9 October 1576, the Gabriel made it back to London, battered and with a kidnapped Inuit man on board. It had been proceeded a few months earlier by the Michael, the scouting ship having been wrecked in a gale. Dee’s knowledge had been useful, but it didn’t take the sailors all the way to their ultimate goal.

But Dee, in his desire to use the latest scientific knowledge in the service of the British Empire (a term he coined), wasn’t about to be put off. He continued to think and write about mathematics, anticipated the invention of the telescope, and amassed one of the most extensive libraries in Europe. He also was deeply committed to what we would now call the occult. As well as maps and cross-staffs, Dee’s house at Mortlake in London, was filled with crystal balls and potions and objects inscribed with all kinds of mystical symbols (some of which can be seen in the British Museum). Dee used this magical equipment to give him visions, to contact spirits, and to hear prophecies given in the secret language of the angels (Enochian, Dee called it). We might see this as outlandish but, in Dee’s era, there wasn’t much of a distinction between mysticism and science. You could spend the morning on complicated geometric equations, then, after lunch, get into a serious conflab with a demon, if you felt inclined.

Dee’s increasingly wild occult experiments eventually led him to a sad end. He fell out of favour at Court and sent many years dragging his family around Europe, trying to use his powers in the service of various kings and emperors. When he returned to London as an old man he found his magnificent library had been destroyed and he lived the rest of his life in poverty. Maybe he should’ve left the demons alone. When he received a letter from Shetland, though, he was in his pomp, at the cutting edge of scientific thinking and with the ear of the Queen. It’s fascinating to think that, as Dee read Frobisher’s letter, he would have imagined it coming from a place at the very edge of the known world.