Peter and Olla

Archivist Brian Smith retells the story of cousins Peter and Olla, two very different characters, who met one notable New Year's eve. Prison, banishment from Shetland, sentenced to serve in the navy and 100 lashes were all to follow for the riotous and mischievous Olla Smith.

At 4 p.m. on Old New Year’s eve in 1805, a Friday night, Peter Adamson walked in the darkness from his house in Fladabister to Greenmow, to buy a few pints of ale.

Peter was 30 years old. He was born in Gord in North Cunningsburgh, the son of Katherine Fullerton and Charles Adamson. Charles, as we shall see, was a disorderly man, often in trouble.

In 1793 Peter had volunteered for the navy. The following year he joined H.M.S. Pylades in Leith as an ordinary seaman. In November 1794, following a cruise off Bergen to watch the French squadron, the ship headed east again, and went ashore at Haroldswick. Refloated, she returned to Leith, and Peter was paid off on 2 February 1795. We don’t know what he did next. He found his way back to Shetland, perhaps after the Peace of Amiens, as Alan Beattie has suggested to me, and got married to Margaret Nicolson in Fladabister in 1802.

The householder at Greenmow was Gilbert Duncan. He was pleased to see Peter, and gave him a drink. He told him that, rather than sell him ale, he would like him to stay. There was going to be a rant, a party, at Greenmow that night. Peter declined. He had promised his wife to come straight home, and he didn’t want to drink in public: he had had a head complaint since he was on the Pylades.

He left Greenmow. Almost immediately he met Olla Smith, his cousin.

***

Olla was born in Mousa in 1771. His mother, Keetie Adamsdaughter, was Charles Adamson’s sister; his father, James Smith, was another unruly Cunningsburgh man.

In 1779 James Smith and John Adamson, Keetie’s brother, my own three times great-grandfather, and two crewmates, had had an extraordinary adventure. Fishing off Mousa they had been picked up by John Paul Jones, the America revolutionary commander, on board his ship the Bonhomme Richard. He took them south with him, and then east to America-favouring Holland. They found their way home a few months later.

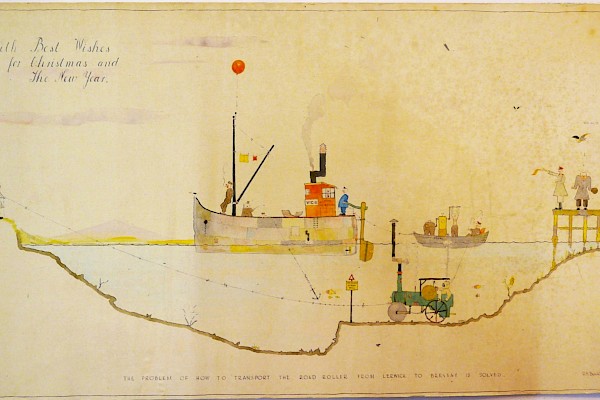

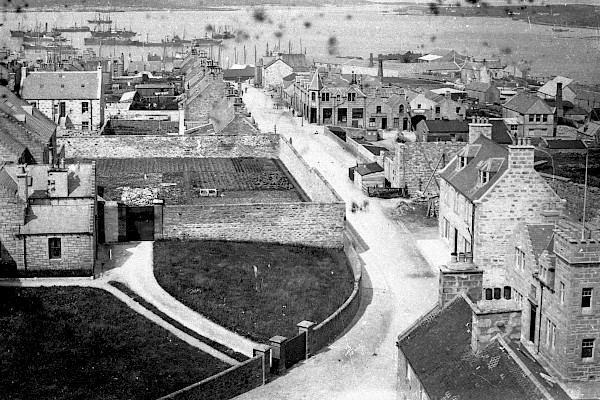

The Shetland that Peter Adamson and Olla Smith lived in wasn’t cut off from the modern world. During the French revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars Lerwick was full of soldiers, and the harbour was jam-packed with naval ships. For a superb account of local British communities during those years, and the ways that the wars changed them, see Jenny Uglow’s In these Times (2014).

Olla and Peter had learned to read and write. In March 1802 Olla, who by then lived at Aness, next door to Greenmow, wrote a letter to Eric Laurenson in Gord, challenging him to a duel. That wasn’t a common kind of letter in Shetland, even in those belligerent times - it has secured Olla a footnote in my old teacher Victor Kiernan’s book The Duel in European History (1988).

Eric petitioned the sheriff to bind Olla, and his brothers, to keep the peace. Keetie Adamsdaughter, John Adamson and Charles Adamson came forward to stand “caution” for Olla and his siblings. It was the first of several episodes of “lawburrows”, as this process was called, involving Olla.

In January 1804, a year before the cousins met outside Greenmow, Olla, with three of his brothers and two uncles, visited Gilbert Duncan. Olla stripped off his shirt and squared up to his host. He threatened to beat him, and refused to leave. The Duncans thought it best to sleep next door, “for the preservation of their lives”, but the following day they approached the sheriff. Again Olla was bound over to keep the peace.

He began to think about going to sea. At the end of the year he engaged to go on a ship to England; but before he embarked a merchant in Lerwick sued him for a debt of 7s.4d. Olla, locked up in the Tolbooth, agreed to pay, and offered to find caution not to beat his creditor. The merchant said to the sheriff that because of Olla’s “notorious character and quarrelsome disposition” he would prefer it if he was bound over. Peter Adamson found caution for him. By the time those arrangements were complete the ship had sailed.

***

Olla followed Peter as far as Aith. They stopped there for a drink. Then they began to head north again, and at Blosta they met half a dozen of Peter’s neighbours.

“Peter,” they said, “are you going to the northward and we to the southward! It’s a pity we could not have a drink of ale before we parted.” There is no record that they said anything friendly to Olla.

The company arrived back at Greenmow. By that time 50 or so people had assembled there. They were dancing and playing cards in two big rooms. Peter said later that “the mixtures of the stale and new ale together with going out of the warm houses into the cold air had operated on his head”. He stepped on a sieve and ruined it. But Gilbert Duncan was still friendly. “What does that signify?” he said. “Come here Peter and sit down alongside of me and take a drink of ale.”

Duncan and others were casting baleful eyes at Olla Smith. Olla had heard, or imagined, that there had been an unfriendly discussion about him the night before at Fladabister. (It’s likely enough.) He confronted James Halcrow about it, and challenged him to fight. He shouted to Peter Adamson, who was nodding off at the fire, that they should take a room each and fight the whole house.

At that moment, about 10 p.m., a dispute broke out in the adjacent room: two men were arguing about who should dance with a woman. The rant was descending into chaos. Malcolm Halcrow shouted: “Whoever means peace keep their seats!” Peter, groggy, said: “I keep where I am”.

Olla took off the handkerchief around his neck in preparation for fighting; Gilbert Duncan grabbed him by the chest and dragged him outside. Most of the adults present followed them to see the entertainment.

Charles Adamson was lurking outside with a baton. He had a grudge. The previous summer he had gone into James Ross’s shop in Lerwick. While there he had used “opprobrious language”, and Ross made a complaint. The procurator fiscal was horrified about the breach of social decorum.

Charles was looking for revenge. He had identified several people who had assisted the sheriff officer during his arrest. He struck Andrew Duncan on his right temple and knocked him spinning. There were blue and red marks above Andrew’s eye and on his cheek the following day.

Olla had stripped to the waist. He began to fight. Five or six men manhandled him into a quarry hole. There was mayhem. Olla’s mother came up from Aness, alerted by the noise, and ran into Duncan’s house to find Peter. “Peter Adamson,” she screamed, “are you sitting here while they are murdering my son Olla in the quarry hole?”

Peter staggered out. He found Olla and Andrew Duncan “entangled together”. “If you are for fighting, Andrew,” said Peter, “fight me and let the poor half murdered man alone.’ He took off his shirt.

But at that stage the tension began to fizzle out of the situation. These people, like most people, wanted peace, whatever the provocation. For a while Gilbert Duncan barricaded his door, to prevent Peter from re-entering, and Peter threatened to break it down. But at length Gilbert let him in. Peter was still angry: he told Andrew Duncan that he would knock his “soapy head about for him” – maybe an expression he had learned on the Pylades. Then someone announced a reel and took Peter as a partner. I suspect that Olla went home.

***

The following morning Peter Adamson’s wife spotted Gilbert Duncan and James Halcrow coming to Fladabister. She advised Peter to ask them if he had done anything amiss the previous evening. They reminded him about the broken sieve. Peter offered Gilbert a sheepskin to make another, but Gilbert said that it was hardly worth it.

Olla Smith, meanwhile, took a different course of action. On Sunday morning he ambushed James Halcrow at Aness and beat and bruised him.

As a result, James, along with Andrew Duncan, went to Lerwick. They entered complaints against Olla, Peter and Charles for assault and riot.

Laurence Jamieson, the sheriff officer, with two assistants, rounded up the accused. It took them a day and night to get them to Lerwick. The weather was bad, but I suspect there was resistance by the three. In the Tolbooth they petitioned for bail. Olla, apparently exhausted, signed with a cross, and Peter could hardly manage to write his name.

Sheriff Walter Scott, who lived at Laxfirth in Tingwall, was unwell. He instructed that the accused and witnesses should come to his house for a hearing. The procurator fiscal called 11 witnesses, the defenders one. The proceedings took two days at the end of February: presumably the accused and witnesses had to stay overnight in Tingwall.

Most of the witnesses had a good word to say about Peter Adamson, and harsh ones about Olla Smith. Even so, none of them made a direct complaint about Olla. He was, after all, their neighbour.

Malcolm Halcrow in Fladabister, who lived an hour’s walk from Aness, said that he had heard a rumour about Olla’s “turbulent disposition”: he believed “with some cause”. Laurence Jamieson said that “it is universally reported in the parish of Cunningsburgh that none of the defenders would be backward in joining a tumult or riot - and that in particular Olla Smith bears the character of a riotous person threatening to fight those with whom he has any quarrel”.

Sheriff Scott found that there had been an uproar at Greenmow, and that it had been excited by Olla, who was thus guilty of a gross breach of the peace. He found that Charles Adamson had knocked down Andrew Duncan with a stick. The procurator fiscal had withdrawn the case against Peter.

Scott decided that Peter should nonetheless find caution to keep the peace, under a penalty of £10 sterling. Charles, he said, was living in mean circumstances, so he confined him to prison for 14 days, and ordained that he should find caution to keep the peace for seven years. I doubt very much if Charles lived that long.

Olla was a special case. Scott committed him to prison, to remain there until a naval ship arrived in Lerwick. He sentenced him to serve in the navy, “in such ship as the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty may appoint”, and banished him from Shetland for seven years – because of “his public bad character as a riotous and mischievous person”.

***

Olla Smith “volunteered” to join the navy on 4 October. In due course he joined H.M.S. Resistance. He nominated his mother Keetie as the recipient of half his monthly pay. In June 1806 he deserted while the ship was in Portsmouth.

Peter Adamson, Olla’s cousin and companion, went back to the navy on 27 September 1805. He deserted on 28 January 1806. What happened to him after that is an interesting question.

For nearly two years Olla hid. In February 1808 he was recaptured, court-martialled and sentenced to 100 lashes. He endured 43 of them and was immediately sent to Haslar Hospital in Hampshire. His complaint, not surprisingly, was a “sore back”. In April he returned to the Resistance, and managed to serve until August. At the end of the year he was back in Haslar, and was finally discharged on 30 December.

Slowly, painfully, he made his way back to Shetland. He arrived in Lerwick in March 1810. His seven years of banishment hadn’t expired, of course. He was recognised, and found himself back in the Tolbooth. He asked for access to a surgeon, and “the indulgence of a fire to warm him”.

The sheriff acceded, despite what he called Olla’s “indecorous and insulting conduct in court yesterday when he was challenged for returning to the jurisdiction”. A surgeon came to see him, “and found him labouring under a chronic rheumatism, for the relief of which he would require warm lodging and warm clothing, with nourishing food and regularity in living”.

On the same day Olla offered his brother John as a cautioner, and promised to leave Shetland again within a month. The sheriff agreed. That is the last we hear of Olla Smith. Broken by poverty, and by naval discipline, he probably didn’t live a great deal longer.

I am very grateful to Alan Beattie for information and suggestions about Olla Smith’s and Peter Adamson’s naval careers, and to Gordon Johnston for walking experimentally from Greenmow to Fladabister during lockdown.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.