Road trip to Orkney

With enquiring minds and a thirst to discover more about the story of St Magnus and the medieval church in Orkney and Shetland we set off for Orkney in October. To better understand our three kirks in Shetland we needed to look at contemporary buildings in Orkney, and to have a closer look at the red sandstone used in their construction.

Our Three Kirks project is a journey of discovery, not just in archaeological and historical terms but with a good measure of geology, offering tangible evidence, which we hope will add another chapter to the fascinating story linking Orkney and Shetland together during the 12th century, and a deeper ecclesiastical union to further the cult of St Magnus.

As noted in our earlier blog, the construction of St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall began in 1137, under the decree of Saint Magnus’ nephew Earl Rognvald Kali Kolsson. Quarries were opened at the Head of Holland and in Eday to provide the stone required for such a magnificent church. Shetland geologist, Allen Fraser explains:

"The Head of Holland quarry, from which we took samples for analysis (see previous blog), is where much of the distinctive reddish-pink sandstone for Kirkwall Cathedral was obtained. Quarried blocks of stone was taken from here to the shore at Kirk Green for dressing by the stonemasons. Red sandstone fragments and an ancient jetty were uncovered during excavations in the 1970s beneath Broad Street, which would have been the old shoreline.

About 390 million years ago these sandstones were being deposited by river systems flowing into Lake Orcadie on the great desert continent of Euramerica, just south of the Equator. The distinctive red colour of the sandstone is due to the formation of iron oxide on the sand grains in the desert environment in which the sands were laid down. Back in 12th century the stonemasons arriving in Orkney from working on Durham Cathedral and Dunfermline Abby would have known nothing of that geological history. However, they would have been delighted with the ease by which they could work the stone into the decorative features we see today.

The yellow sandstone that contrasts so well with the red to give a decorative polychromatic effect, and a delight to the eye, was probably quarried on the island of Eday. Antiquarian Sir Henry Dryden considered the stonework in Kirkwall Cathedral to be the "finest example in Great Britain of the use of stones in two different colours"

https://www.stmagnus.org/index.html

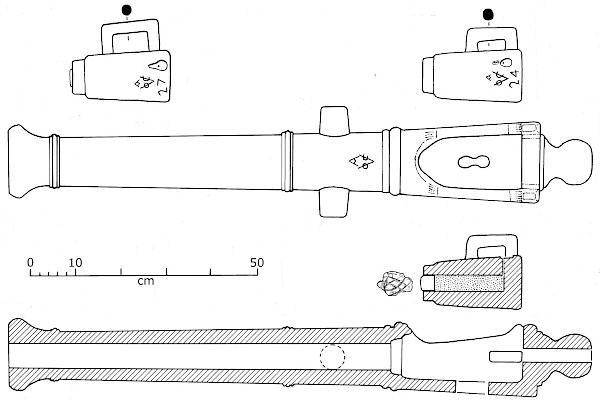

While in Kirkwall, Allen measured many of the ashlar blocks in the cathedral to compare them to our Shetland examples, with the hope of supporting the theory that the blocks used in our three kirks were shipped to Shetland ‘ready-made’ by the same stonemasons!

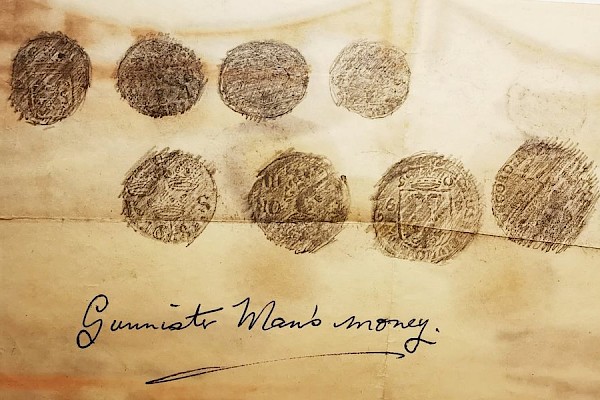

While Allen measured in the pouring rain I took the chance to visit the Orkney Archives to soak in the fantastic drawings and plans of various Orkney churches done by Henry Dryden during the mid-19th century. The archives held here are a treasury for any researcher (especially while it’s raining).

Our Orkney adventure also took us to visit other churches including St Magnus on Egilsay, where fragments of red sandstone could be seen in one of the gable ends and also built into the churchyard wall – this has to have been brought into the island at some point in the past. We need to be careful not to jump to the conclusion that it may have been used in the original construction of the kirk during the 12th century. Allen took Shetland samples with him to compare with Orkney examples and as you can see from the image below, compared to a stone in Egilsay kirkyard wall they look identical.

The next morning (yes, it was still raining) took us to the tidal island of Brough of Birsay where a Late-Viking church and associated settlement sits defiant despite the thundering gales that bluster its solid foundations. Was this Orkney’s first Norse church, built by Earl Thorfin the Mighty? He was Grandfather to Saint Magnus, a Viking raider and pillager turned good-guy (more about him next month). Or, was Thorfin’s Christchurch situated underneath the modern church, dedicated to St Magnus, in Birsay village. There is much red sandstone to be found here and a beautiful 13th century lancet window was rebuilt into the modern church.

http://www.birsay.org.uk/heritage.htm#stmagnus

By Sunday the sun had come out (a divine intervention I like to think) so we explored the round kirk at Orphir, dedicated to St Nicholas and supposedly built be the redeeming Earl Haakon Paulsson (remember him…the treacherous cousin who ordered the cook to kill our Saint Magnus) following a pilgrimage to Rome and Jerusalem c. AD 1120 (no signs of red sandstone here though).

Then it was south to St Mary’s Kirk in South Ronaldsay which sits on an ancient site at Burwick. It is surrounded with history, including a broch settlement, where Pictish kings are thought to have held their ceremonies of coronation, placing their royal feet into the ‘footprint stone’ which still survives thanks to its safekeeping within this delightful but now derelict church…and yes, you guessed it…there is red sandstone built into the fabric here too!

https://canmore.org.uk/site/9560/south-ronaldsay-st-marys-church

Alas, with still much to do, our short weekend and the decreasing October light limited our activities for this time. Another trip in the spring is a must!

Next month we will take a closer look at the three Earls who are instrumental to our story, Thorfin the Mighty, who brought Christianity to the region, Magnus Erlendsson the Martyr and his nephew Rognvald Kali Kolsson. And…fingers crossed….our results from the British Geological Survey may be back so watch this space!