Who's afraid of the njuggel?

Halloween wouldn’t be the same without a fair sprinkling of supernatural beings such as ghosts, vampires and werewolves, but centuries ago in Shetland, they were more afraid of the njuggel.

If you want another thing to be afraid of on the spookiest night of the year, look no further than this most deceptive of creatures.

Dr Ian Tait compares the njuggel of Shetland, which has a Scandinavian tradition, with the kelpie of Scottish folklore:

There is a degree of similarity in the two traditions, in that both were a supernatural creature that took the form of a horse and its habitat was fresh water, but there was no shape-shifting with the njuggel”. The njuggel enticed people. It was an approachable animal and when it came trotting up to you, your inclination was to hop onto its back. As soon as you had done, it galloped off to the nearby loch and pitched you into the deepest water.

Something people might not consider is the wider context of how the njuggel could engineer this in the first place.Today we travel around on foot or in a vehicle and if we’re going off a track that’s usually the exception, not the rule. The Shetland of bygone centuries was a landscape which didn’t have any roads at all, and people were roaming the moors 12 months a year for all different purposes, such as harvesting rushes, transporting peat or driving sheep. Not only that, but the landscape was open in a way it isn't today. Now, it's carved-up with fences but it was formerly an open landscape and the moors were common grazing, so cattle, sheep and geese were there - and horses. Therefore, it wasn't unusual for people and horses to be wandering around in the hills.This often went on at dusk or even by moonlight when you could see clearly where you are going, so seeing a horse wasn't an odd thing. I guess this is why the njuggel was able to do its dastardly deeds because it seemed just another horse! However, when you got near to it, its unusual form was seen, especially the flowing tail, which was supposed to be circular in shape. It was an attractive animal that’d make you pause and take more notice than you’d normally do when encountering any other horse.

The njuggel would only make itself visible to you at dusk, when it already close to water, and if you were enticed onto its back, you were a goner.

As is often the case with folklore stories, there was more to it than a supernatural creature doing someone harm, because there was an extra twist of luck. Quick as the njuggel was galloping to the water, if the rider had enough time and presence of mind, they could utter the creature’s name, and this would save their life. That was because on hearing the cry to halt, the creature lost much of its stamina, and as it slowed to a trop the unwilling rider had chance to hop off.

Even when the njuggel wasn’t seen, people on the moors took care in the long hours of winter darkness; the time of year when grain milling was done. Watermills were on the moors, and always at freshwater, i.e. the ideal haunt of the njuggel. If anything went skew-whiff with the mill apparatus, the feared njuggel was suspected, and the miller dropped a peat ember to scare it off. To be even safer, the person milling the grain could scatter a gift of meal onto the loch as a gift for the njuggel, in the hope it’d be satisfied with the offering enough to keep its distance.

The prevalence of the belief in this old Scandinavian tradition can be seen by placenames throughout the islands; lonely inland lochs like Njuggleswater in Tingwall, Njogershun in Northmavine and Nuckrawater in Whalsay. You can read more here

This interview was recently published in the Press and Journal.

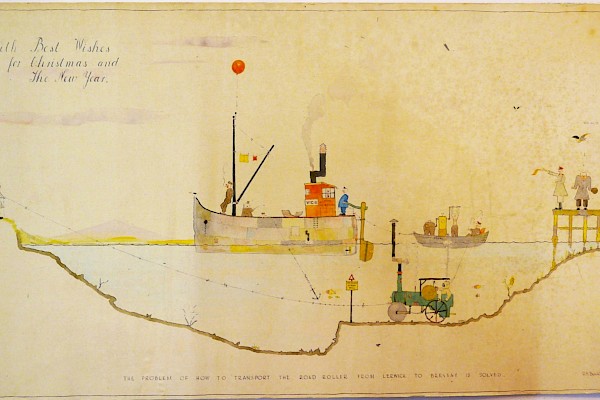

Illustration by Davy Cooper from 'Folklore Whalsay and Shetland' by John Stewart.