The New Year, 1872 and the Truck Commission

The New Year of 1872 began in a special way in Shetland. On the first of January Sheriff William Guthrie began hearings in the Queens Hotel, the Shetland part of a Royal Commission into the truck system. The John o Groats Journal reported that a number of people came forward, some to give evidence, some out of curiosity.

Truck was a system of debt bondage that troubled Victorian Britain. Typically it lives in places with few or single industries, and/or powerful landlords. It is especially associated with coal mining. There’s a depiction of it in Emile Zola’s novel, Germinal, although Shetlanders might more associate it with Sixteen Tons, a song by country singer Merle Travis (1917-1983).

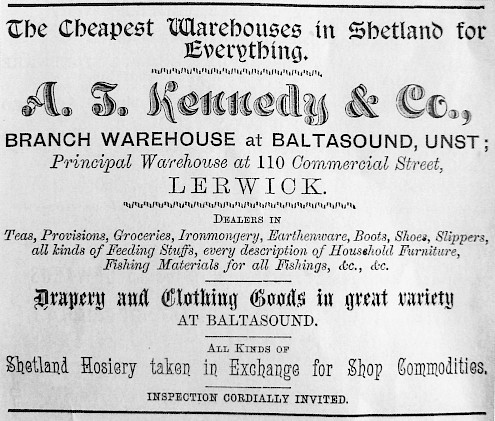

Truck evolved in Shetland after the disastrous and starving decade of the 1690s. The fish were sold, people were paid by landlords or merchants, and had to buy their goods from their businesses. No shopping around. It was a kind of cashless economy in the sense that people rarely saw cash. In fact, they could find it difficult to establish how much money they had. When they did, they often found debt. As Merle Travis put it in his song -- I owe my soul to the company store. Unsurprisingly, the truck system was open to considerable abuse.

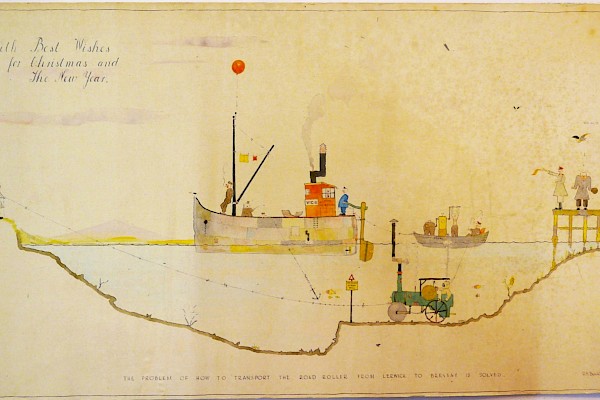

Guthrie got around Shetland, from Boddam in Dunrossness to Baltasound in Unst, producing 456 pages of closely printed double column text, as Shetlanders expressed their views on the system that dominated their lives. He asked 17,000 questions. The first day, 150 years ago, can tell us a great deal.

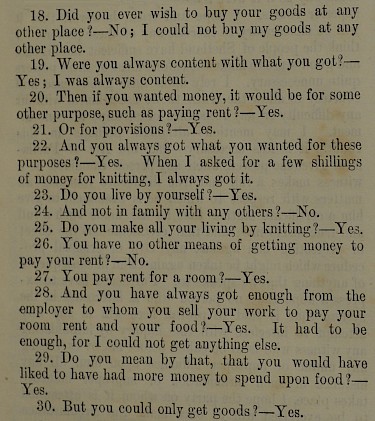

The first witness was Catherine Winwick, who lived by herself and knitted for a Mr Linklater. She may be the Catherine Winwick (1834-1876) from Uyeasound in Unst, who lived in Reform Lane in Lerwick, but her statement doesn’t give that kind of personal information. Her dialogue is cautious, as if she was afraid to offend. She probably was. Consider this, when Guthrie asks her about being paid in money –

Do you mean that you knew if you had asked for it you would not have got it?--I don't think I would have got it all in money; I never asked him for it all, but I always got what I asked for. If I asked him for a few shillings of money, he always gave it to me.

While she got some cash, she was largely paid in goods, among them nine yards of white cotton at 8½ per yard. Catherine had to pay rent, probably where much of her very limited cash income went -- It had to be enough, for I could not get anything else. When Guthrie asked her if she would have liked to have had more money to spend on food, she answered unequivocally, Yes. But she didn’t get paid in perishables.

There were nine witnesses that day, seven of them women, really the first time we get a body of Shetland women whose lives are documented to any extent. The final witness, a man, Simon Laurenson of Cunningsburgh, spoke for only a short time, but got his point over -- We want to know, as British subjects, whether, if we pay our rent annually, we are entitled to our freedom.

Did anyone get their freedom as a result of the thousands of words the commission collected? Although there was a report, the sad answer is no. The Shetland system was a difficult one to crack, especially as the trucked Shetlanders were self-employed, not employees. The Sheriff did put his finger on it his report though -- It is plain that the prevalence of truck is due in no small degree to the habit of dependence, or submission, which the faulty relations between landlords and tenants have fostered. And then -- I may at least be permitted to hope that, in any reform of the land tenancy laws of Scotland, the case of Shetland will not be forgotten.

Shetland wasn’t forgotten when reform of the land tenancy laws came from another commission, the Napier Commission in 1883. Witnesses were not so awed by authority and magnates then, and some were quite combative. A lot had changed in just over ten years. The herring industry operated quite differently to the traditional open boat fishery most men were employed at in 1872.

That was the men, what about all those women whose lives were document? In the knitwear industry the practice of exchanging goods for hosiery carried on. There was a second mini-truck enquiry in Delting in 1887, but the system, amazingly, carried on up to World War Two. The Shetland Hand Knitters Association and A.I. Tulloch are held to have played a major part in finally toppling it.

Truck has gone from Shetland, and the 150th anniversary of the enquiry is a time to reflect on the powerful body of testimony left for researchers thanks to Sheriff Guthrie’s assiduity, and thecourageous but often diffident witnesses. It hasn’t gone from the world altogether, and is alive and well in parts of Africa, Asia, and South America. Every now and again, it crops up in a TV interview with a desperate migrant, trying to be entitled to freedom, like Simon Laurenson.