The Shetland Archives - behind the searchroom

In the Shetland archives, we are lucky to have an enormous collection of our recent-forebears on tape. There are recordings of men and women who lived through wars, who spent their lives on little crofts, who survived fishing disasters and who could tell stories their own grandparents told them.

In our audio archive, which is expertly looked after by Angus Johnson, we hear Shetlanders telling us what the place we live in used to be like.

About ten years ago, I set off for Bressay, with the intention of adding to this rich collection. The interviewee was one of my favourite Shetland poets, Stella Sutherland (1924-2015). A few days earlier, I had phoned Stella, who I’d never met, asking if I could come and see her. She told me that she had read some things I’d written for the New Shetlander (which I was flattered to hear she liked), and that she’d be happy for me to come along.

Armed with a digital recorder, I turned up at Stella’s house and was ushered into the kitchen, where, during the next half-hour, I got through two huge bowls of soup and at least four pieces of buttered toast. Cups of tea followed and, swittling, but still able somehow for a custard cream or two, we started to speak. Stella told me about her early life in Foula, and about how she remembered the making of Michael Powell’s 1937 film The Edge of the World (there was, if I remember rightly, a poster from the film on the kitchen wall); we spoke about her writing; about the New Shetlander and the other Shetland authors associated with the magazine; we spoke about other poets we both liked (I think Larkin was one, but now I’m not so sure); and we spoke about the religious faith that was obviously a source of strength and comfort for Stella. After speaking for about three hours, I set off for the ferry, carrying a signed copy of Stella’s excellent poetry pamphlet Joy o Creation (Hansel Co-operative Press, 2008). In the other hand, I had the recorder, which had never been out of its bag.

Part of me now regrets not setting up the machine and recording the conversation. In phoning to arrange the visit, I think I wasn’t very clear that I intended to do so, and, as we spoke, it was hard to rewind to a point where a more formal interview might be carried out. But another part of me is glad the recorder stayed where it was (slid, tactfully, under the chair). The presence of the microphone on the kitchen table, the list of questions I had prepared – can you tell me about your early life? – the idea that what we said would be kept for posterity, these things would have changed the whole dynamic of what, in my memory, remains a treasured afternoon.

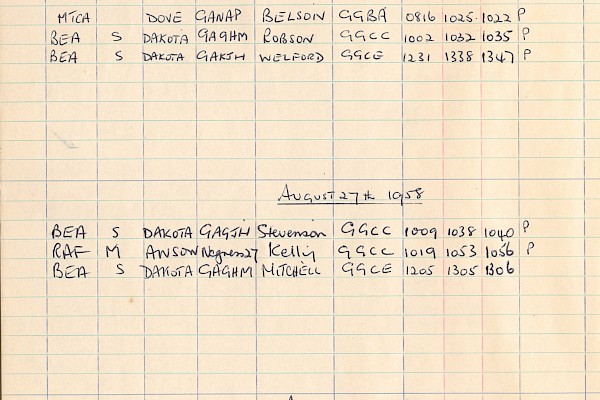

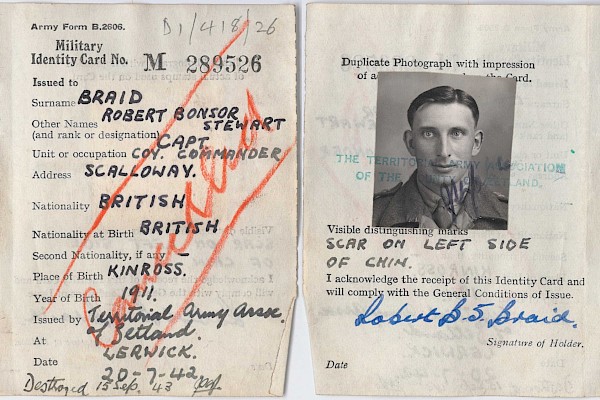

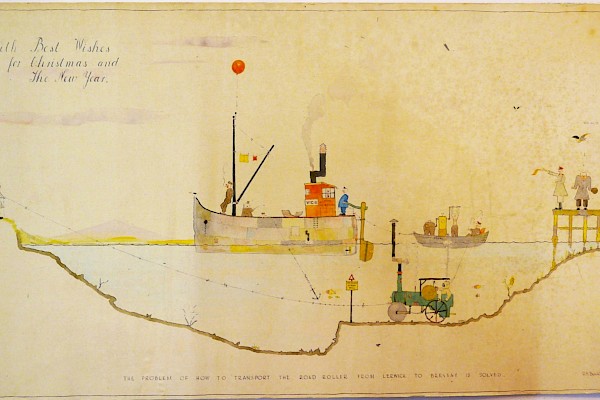

Thinking back to this makes me think about what actually ends up in the archives. In the archives we do our best to preserve and make available good historical sources, but often the things we keep are partial, fragmentary, accidental – the letters somebody didn’t want to throw away, the notebook that was found when a grandparent’s house is cleared out. If I had made a recording that day in Bressay, we would have had a good source for anyone interested in the life of a remarkable Twentieth-century Shetland woman; but, even so, we would never have had the complexity, the fullness, the triumphs and dramas and disappointments of the life itself. Even with the words of a person, even with their own words, the view we get of a life when we look at the archival record is never the full story. Our collection is large and varied – from Sixteenth Century land deeds, to Twenty First-Century newspaper cuttings – but the material we preserve is only ever the jumping off point for the stories our island history can tell. For some of those stories, for some parts of Shetland’s history, we have richer sources than we do for others, but no matter what material survives, we only ever have traces and echoes of the past.

In Stella’s case, those echoes can be found right across the archives collection. There are the early pieces she wrote in the handwritten notebooks that were circulated by the Shetland Poetical Circle between 1943 and 1947 (archives reference number D9/174, if anyone would like to see them), her first published work in Manson’s Shetland Almanac and Directory in the same decade, the poems and stories she published in the New Shetlander and Shetland Life for the next seventy years, and the letters she sent to contemporaries like John Graham. For anybody interested in one of Shetland’s best poets, the archives offer plenty of chances to enjoy the work Stella did.

But, as I say, any life only leaves traces in the historical record. Sometimes, those traces go no further than the letters and diaries and recordings that contain them. Others, though, are corralled and sifted by researchers; gathered together and interpreted until they can be brought into the light. One of the most gratifying things about working in the archives is seeing the books, articles, PhD theses, and family histories that would not exist were it not for the dedicated people who come to our searchroom and sit for hours and hours putting together the pieces of whatever historical jigsaw they have decided to take on.

This, maybe, is what makes the archives an unusual, perhaps even a challenging, kind of place: the archives is a place that, to get something out, you have to put something in. Nowadays we’re all used to Googling something and getting a quick answer but, to answer a tricky question about Shetland’s history, to find a piece of obscure local information, to build up a picture of lives that have been lived here, there is often hard work to be done.

Academics, genealogists, local historians, biographers all come to the archives and try to make what they can of the records we look after. As archivists we try our best to provide the richest resources possible, but the work we do is only part of what’s required to really bring the past to life. The collections we care for are nothing more than the building blocks (sometimes incomplete and fragmentary) for the work archives users do. It is a constant joy to see folk doing that work and, once the pandemic ends, we’ll be very happy to welcome them back.