Why hunt fowl?

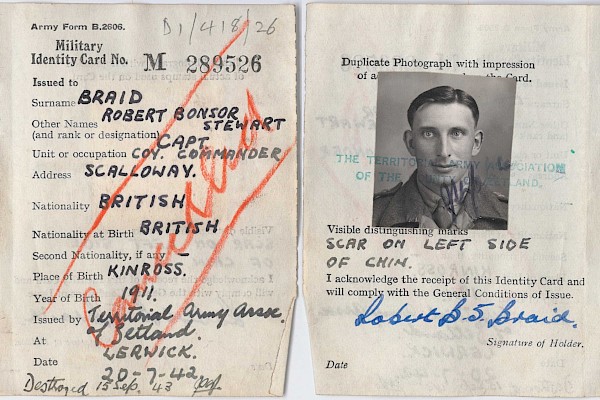

As part of the Between Islands project, Shetland’s new online exhibition, ‘Fair Game’ examines three customs that are now sometimes viewed rather emotively – fowling, whaling and peat cutting. Here, curator Ian Tait takes a closer look at the practice of hunting seabirds and eggs, and how historically North Atlantic islanders relied on seafowl for food and many other practical uses.

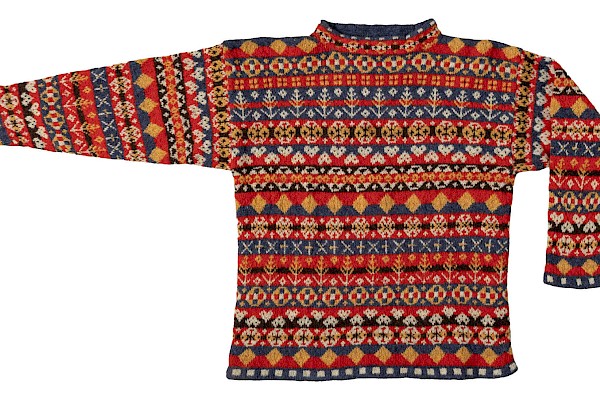

North Atlantic islanders relied on seafowl for food over millennia, broadening their diet by extending limited resources. Birds were roasted when fresh, and salted ones were boiled throughout the year. Feathers had many uses; soft ones for bedding, quills in toys, bright ones for fishing lures. St Kilda’s folk depended on birds like folk elsewhere used fish and seals: islanders made bait from puffins, lamp oil from fulmars, shoes from gannets.

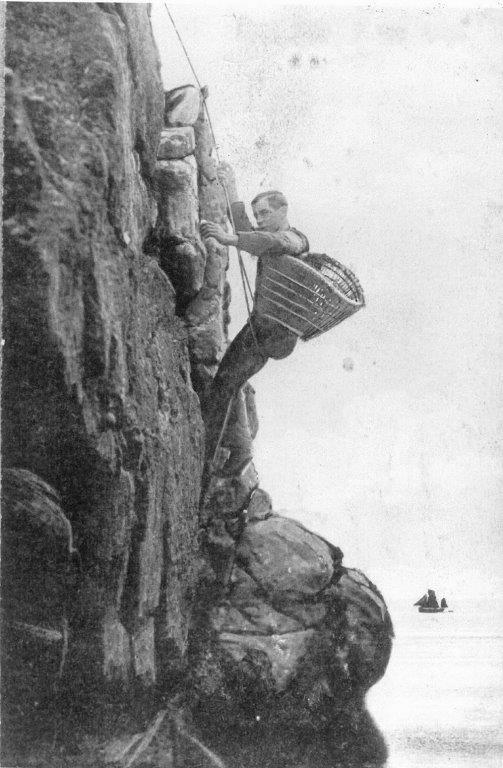

The inhabitants of St Kilda, in the Hebrides, depended on birds more than any other society in Europe. They had to descend the island's terrifying cliffs, their life depending on a rope and their bare feet, to net fulmars and to snare gannets. Birds sustained people for thousands of year - providing food, bedding, thread, footwear, medicine.

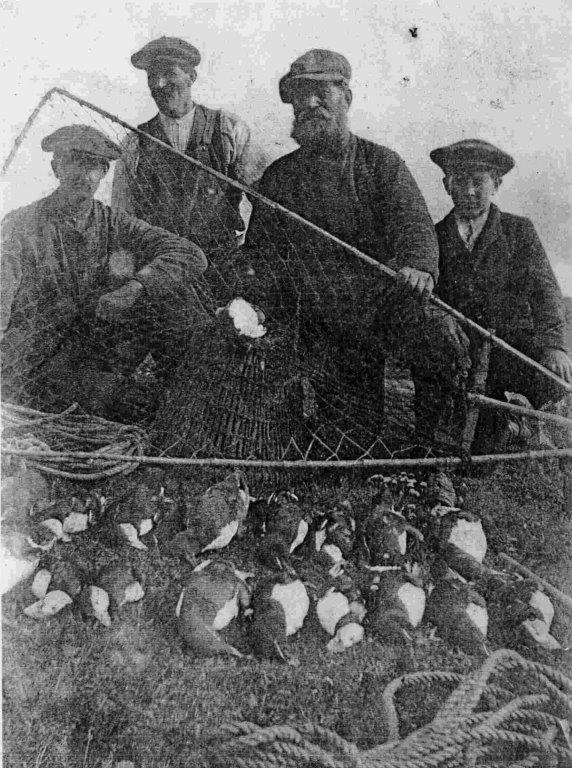

Northern and Western islanders caught birds using similar methods – snares, nets, and ropes. For cliff-laying birds, operations were dangerous, and men on the clifftop lowered someone over the precipice on a rope. Cliff fowlers carried a basket for eggs, and birds were tied around the man’s waist. George Low described operations in Foula in 1774: “They never trust much to the rope nor stake. Once they have got footing, they depend more on their own climbing than any rope… Few who make this practice for life die a natural death.” People only targeted particular species, because it was vital to not overexploit resources that humans partly depended on for survival.

Gathering birds and their eggs was a seasonal part of every Shetland family's life since ancient times. Depending on local geography, people went off to holms by boat, or went down cliffs by rope. The fowler carried a basket for eggs, and often a pole with a hook to manoeuvre towards a nest.

However, from the 19th century, visitors collected scarcer species for stuffing, and islanders were happy to sell specimens. These depredations affected the rarer species not required for subsistence needs. Eventually, legislation protecting birds was introduced. The only communal fowling left in Britain is the Lewis gannet hunt, protected by law since 1954. Modern threats - habitat loss, pollution, overfishing - pose more harm to birds than fowling did. The Faroese are the only islanders where traditions survive, and annually around 150,000 birds are harvested. Battery hens are cheap, and safe to acquire, but are they more ethical?

Seabirds and people lived in balance, and thousands of eggs were eaten each year. Northern and Western Islanders had largely abandoned harvesting eggs by the time gathering them was banned in Britain in 1954. The Faroese still collect them from the wild for food, but British islanders are largely too genteel now for seafowl eggs, even it was legal!

Listen: Ian Tait will be interviewed for Radio Scotland’s ‘Sunday Morning’ live show on Sunday 31 January at 10.00am, where he will be discussing the Fair Game exhibition and together with a panel discussing what causes society to change its behavior, and how/if it should be changed more.

Find out more: Follow the links to find out about the Between Islands project, Shetland’s new online exhibition, ‘Fair Game.