550 Years Ago: how Shetland became part of Scotland

A fortnight ago some women and men from the South Mainland of Shetland marched in Glasgow with torches. They were commemorating the 550th anniversary of the moment when Shetland (and Orkney) became part of Scotland.

Over the years there has been a lot of discussion, and confusion, about what happened in 1472. But the solution is very simple. The King of Denmark wanted to get rid of Shetland and Orkney, and the King of Scotland wanted to acquire them. The Danish king took a very laid-back attitude to the situation, and James III of Scotland acted very forcefully.

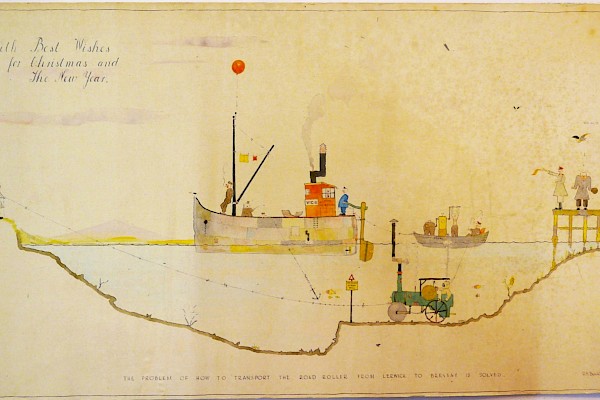

The process started in 1468 and 1469, when Princess Margaret of Denmark married James. Margaret’s father, Christian I, couldn’t afford a dowry. So he mortgaged first Orkney, and then Shetland, to his new son-in-law. The day after he disposed of Shetland, in May 1469, he wrote to his Orcadian and Shetland subjects. He told them to be obedient to the king of Scots, and to pay their taxes to him every year, until he (Christian) could afford to pay redemption money.

There is no evidence, and no likelihood, that Christian had any intention of redeeming the islands. After May 1469 he paid no more attention to them. But James III of Scotland didn’t neglect us. During the next few years he acted decisively to bind Orkney and Shetland closer and closer to Scotland.

James annexed Orkney and Shetland to his crown on 20 February 1472. He promised that they shouldn’t be given away in time to come to anyone, except one of the king’s legitimate sons. His plan was that the islands should be governed by the Scottish crown, and administered on the king’s behalf by his own governors and tax-collectors – while leaving open the possibility that they might be gifted to a respectable nobleman sometime in the future. So in August the same year James appointed the bishop of Orkney, Andrew Pictoris, as his agent in Orkney and Shetland. King Christian didn’t complain.

And something else happened, again in 1472, that was equally far-reaching. Six months after the annexation Pope Sixtus VI created an archbishopric in Scotland, based at St Andrews. He attached the bishopric of Orkney to it. At a stroke the ecclesiastical affairs of Orkney and Shetland had been taken over by the church in Scotland, just as their royal administration had been.

Shetland and Orkney still had their own legal and administrative institutions: their own parliaments and officials, especially the elected officials called lawmen. No-one tried to change that for a long time. But an event happened in 1476, four years after the annexation of 1472, that gives us a hint how things would change eventually. That year James III’s exchequer got a bill from the lawman of Orkney for his salary: not just for that year, but for the four years since 1472. James paid up.

But James made a significant caveat: that the salary should only be paid from then on with the king’s special permission. There were no lawmen in Scotland. James was willing to countenance such an official in Orkney, but he intended to keep an eye on him. After the 1540s there were no more Shetland or Orcadian lawmen.

Just as Christian had let Shetland and Orkney slip through his fingers, hardly caring, so did the archbishops of Trondheim let them escape as well. In the early 1520s one of the archbishops sent a German clergyman to the papal court to find out why the islands were no longer part of his jurisdiction. He burrowed for a long time in the archives, and at last found Pope Sixtus’s bull of 1472. He sent a copy of it to the archbishop, and gave him some advice about how to get the islands back. But by that time it was too late. Shetland and Orkney had been part of Scotland for fifty years.

Read part 2 here - 550 Years Ago: how Shetland became part of Scotland