A reminiscence of a traditional Shetland wedding

When lockdown came, one of our first sad tasks was to tell two couples who’d planned a wedding in the museum that it couldn’t happen. We’ve had more weddings than we ever expected on the premises since we opened in 2007 (56 to be precise), and many photos taken around the Hay’s Dock site.

Weddings brightened a Friday afternoon, with the buzz of people in their wedding finery, glasses in hand. The museum weddings were carefully arranged affairs, sometimes even elaborate, needing a great deal of work by the staff here. Of course, wedding customs in Shetland have changed a lot over the past couple of centuries

George Stewart (1827-1911), author of Shetland Fireside Tales, wrote a reminiscence of the first wedding he attended, in the Shetland Times in 1875. He was twelve, which puts it around 1837. Almost certainly he was invited verbally by someone – printed invitations started later on. The wedding, involving a Bigton couple, meant a trek of six miles for George. Unsurprisingly, Shetland weddings in that era involved processions. They assembled people together, and crucially, got them all in the right place at the right time. There were no roads to speak of in the 1830s.

With a fiddler at the front, a married couple, usually relatives of the bridegroom, led off, followed by the bride and groom. Others followed, paired off, the twelve year old George with a lass of seventeen. He was fairly pleased, her feelings are unrecorded. There was obviously some possibility for cringe in this process. The last couple, the tailsweep, were relatives of the bride and groom, and at the very end was a man with a firearm, the gunner.

This wedding procession probably got a bit ragged, the weather was bad, the protagonists got soaked – I felt small streams stealing down my back. Shetland weddings in this time were often held in the winter. The fiddler didn’t risk playing, and the gunner kept his powder dry. They stopped at a house near the manse at the Ness, and dried off round about a roond aboot fire – one in the middle of the room with the smoke going through a hold in the roof. Whisky and a tune from the fiddler – the Bride’s March -- helped a lot too.

Recovered, the ceremony took place in the manse kitchen, the fiddler played the Bride’s Return and the gunner fired shots to ward off mischievous spirits - the hillfolk, the fairies, and the trows. Then they made for the bridegroom’s house and further celebrations. Plenty of food, and plenty of drink. A kind of broken up oat bannock, probably sweetened and carried in a skin sieve, was thrown over the bride’s head. George said the pieces were scrambled after so they could be put under pillows to dream on.

With the fiddler seated in the kiln door – a vantage point -- dancing started. Under the magic influence of the fiddle you find it a physical impossibility to keep your feet at rest said George. Tunes included Scallowa Lasses, Soldier’s Joy, and the Fairy Dance. Deil Stick the Minister, which hadn’t been tried in the minister’s earshot, got unleashed. While there wasn’t much variety in the format of the dances, George Stewart noted that a lot of different steps were improvised. With hootch and hooches, it all went well.

This wedding had guizers, a specific sort – skeklers (or scuddlers in the article) announced by a gunshot. Six of them, dressed in straw costumes and ribbons, their leader whirling a besom to make a noise. He danced with the bride, the others choosing partners. After whisky and dancing they left, identities unknown, faces still masked.

The good times had to end, and the fiddler was paid with a collection. George slept in the barn along with a number of others, both sexes, settling down among the straw. Sometimes this is called a langbed. He emphasised that everyone’s behaviour was impeccable. Then he walked home in the morning, the weather had turned fine.

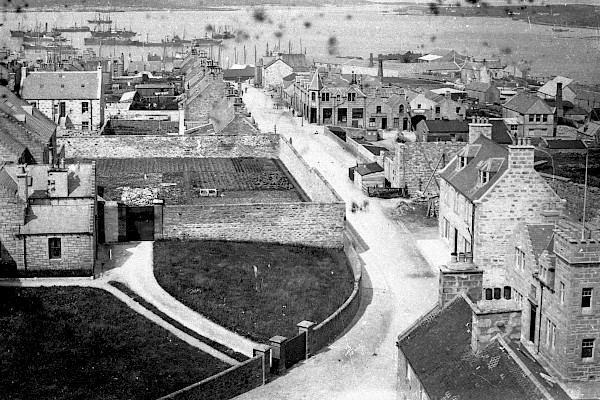

Things were still going on in this way when George Stewart wrote his account. By the end of the nineteenth century they were changing. Some couples chose to get married in Lerwick, given the facilities there. Rural halls meant weddings could take place in larger, more formal spaces, and after World War One the traditions that George Stewart catalogued largely ended. The procession idea attracts some couples and gets revived from time to time. It makes a striking photograph, but there are no more six mile marches.

George Stewart's article Recollections of a Shetland Wedding can be found in the Shetland Times, October 8, 1875, and is also reprinted in Peter Cooke's book, The Fiddle Tradition of the Shetland Isles, available to download.