Accounts with Women Labourers

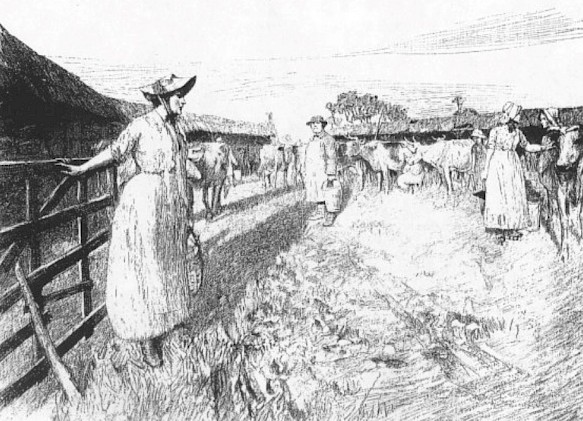

Thomas Hardy, probably the Victorian novelist most familiar with the grit of rural life, described the work of his agricultural labourer heroine in Tess of the d’Urbervilles, bending to her task and fate in turnip field -- or the neep rig if we prefer.

They worked on hour after hour, unconscious of the forlorn aspect they bore in the landscape, not thinking of the justice or injustice of their lot. Even in such a position as theirs it was possible to exist in a dream. In the afternoon the rain came on again, and Marian said that they need not work any more. But if they did not work they would not be paid; so they worked on.

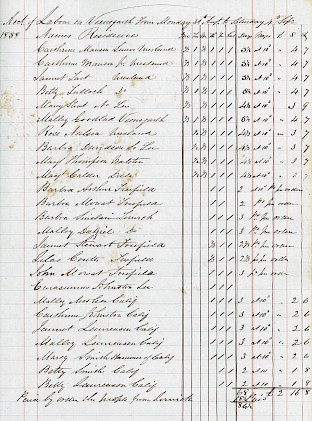

Women like Tess aren’t greatly remarked on in records. Generally, records relating to women and their tasks are many fewer than those for men. There is though, a slim volume in the Hay & Company records, D31/20/9 Accounts with women labourers at Veensgarth. At that time the farm was the property of George H.B. Hay, and was run by a farm manager, George Keith, from Watten in Caithness.

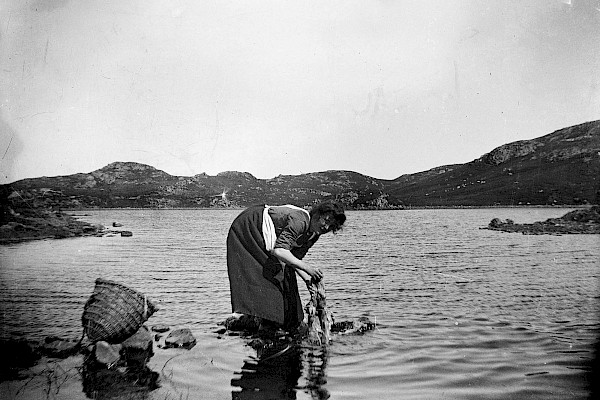

Shetland women played a large part in traditional crofting agriculture, with seafaring men away at crucial times of the year. There have never been many farms in Shetland anyway, and the image of work there is of robust men working hard. While units like Veensgarth in Tingwall employed a number of full-time male workers it also used casual workers, men and women, hired daily.

For a short period from 1858 to 1861, the account book lists women – along with a few men and boys – usually coming into the farm from nearby settlements like Uresland, Braewick, and Califf. Nearby in modern terms, but not so easy then on foot, over unmade tracks, often working as daylight permitted, leaving home in the half-light, going home as it darkened.

In September 1858 Henderina Manson, Bessy Robertson, and Elizabeth Johnston came in from Whiteness, and for two days work at ten pence a day, they got one shilling and eightpence each. Whiteness is some miles away, and the document doesn’t say whether they walked in each day or lodged with someone for their 1s. 8d.

It isn’t always clear who the women are, although they can be cross-referenced with the 1861 Census. The three Whiteness women are a bit mysterious, but Catherine Manson, senior and junior, of Uresland, are easier to find. In 1861 one was 53, the other 25, giving their occupations as agricultural labourers. Both worked four and a half days from Monday 27 September 1858 to Saturday 2 October. Eight pence per day gave them three shillings each.

The account book doesn’t say what they did. It was mundane to mention. It isn’t difficult to imagine the work – turnips do get a mention on one page – harvest work with hay and oats, taking up potatoes, clearing stones from rigs, and so on. Many a day with a bent back, there is no doubt of it.

As far as I know, there was no Shetland Hardy to describe Shetland's women labourers as they worked their way through the landscape, rain or shine - if they did not work they would not be paid. On the good days, of course, there was more fun and fellowship that the pennies paid per day suggests. On the poor days when activity wasn't enough to warm a body, the frozen wet weather would have perished poor hacked hands.