Floss

The second Covid Summer hasn’t been as good as the first. Not cold, but overcast, foggy, misty and moist, with the warm and watered greenery doing well enough. Probably, floss has had a good summer.

That’s a word now associated with sheepdog names and delaying dental decay. For a long time it was an important word in Shetland, a name for rushes, Juncus effusus and Juncus conglomeratus. How the name comes about is unclear, although it does appear in Jakobsen’s dictionary of Norn words.

Floss favours the poorly drained land Shetland has no want of. It retreats from the edges of deeply cut drainage ditches, leaving more grass for the sheep. Reseeding and lime too, have improved grazing and cut down on the floss habitat. A useless plant then?

In the pre-gaffer tape economy of the past things were fastened mostly by tying or nailing. Cordage, mostly hand-made, was perpetually short and expensive. Shipwrecks, the Lord’s bounty to the poor, were highly regarded for wood, but were also a bonanza of rope.

Floss could thatch a roof if straw was short though held to be inferior because it was slippery. Thatching is more than straw however, it needs rope to help keep it on. In Shetland the word was simmonds. Again in Jakobsen, Old Norse had a word simi, a rope or a cord. Floss wasn’t the only cordage source – heather was best, and bent (marram grass) can make ropes too. Floss was ubiquitous however, and the other two aren’t. It had another significant use, it was an important component in kishies.

People would gather floss, dry it, and make simmonds during the winter. An image springs to mind of an old man, slowly weaving a rope out of floss baet (a bundle), perhaps learning a young boy at the same time, perhaps a koli (a lamp with a split rush for a wick) giving some light but more likely a blazing open fire, the wind and rain beating on the thatch roof, held on using the simmonds. Women learned the craft too, but their hands were mostly kept busy at their wires. The world of floss.

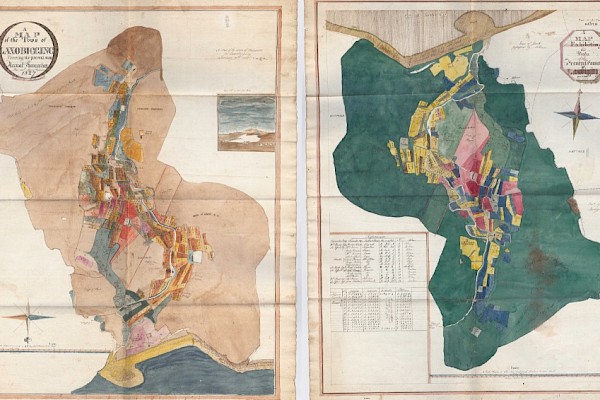

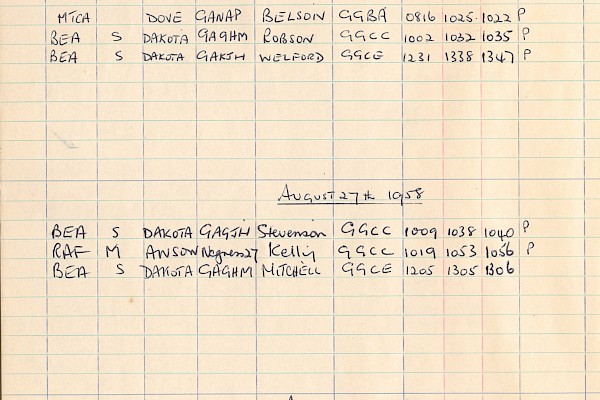

Making simmonds is laborious, fifty centimetres is a long rush, and it takes a lot of rushes to make a worthwhile length. There are limits to the amount of floss even boggy Shetland can produce. Floss had to be shared out, and sharing wasn’t for everybody. In 1829 the lairds William Bruce of Bigton and John Bruce of Sumburgh charged a few people with cutting floss before the twelfth day of August, the customary date to start cropping it.

In 1771 there was a rammy in the Clift Hills -- SC12/6/1771/3 – if you want to read it in the Shetland Archives. Some men from Burra attempted to cut floss the Cunningsburgh men believed was theirs. It was something of a committed encounter, but contrary to at least one tradition, no-one was murdered. That isn’t to say it wasn’t thought about.

The simmond supply problem was solved in the later nineteenth century. The industrial revolution made all kinds of cordage cheaper in real terms. Shetlanders moved away from thatch roofs and kishies, and their requirements. In 1885 A.J. Leask advertised and effective floss simmond substitute – coir rope made from coconut fibre.

Coir, known in Shetland by the original Malayam term kayar, took off in Shetland. Kayar simmonds were well used, often holding down outdoor hay storage, skroos, stacks, and desses. That phase lasted well into the twentieth century, until it too was replaced by new practices, and artificial fibres. So far, floss hasn’t made a comeback as a natural fibre.