Love letters from the past

Since we’ve got to St Valentine’s Day the time has come to consider the Shetland Archives holdings on the subject of love. Do we hold any love letters? The simple answer is YES! After that we have to add qualifications. We don’t have that many. Unsurprisingly, potential donors consider that kind of item as private, and destroy them or keep them in the family. Some think they’re of no interest to anyone else, which isn’t strictly true.

Love letters don’t mean a successful relationship. We have some, written on expensive, romantic stationery. Beautiful paper and fine sentiments, surviving because they were engrossed in Sheriff Court proceedings when the potential wife sued for breach of promise to marry. The correspondence has long outlasted the commitment. There were enough proceedings of this sort for the late Mary Prior to write a book – Fond Hopes Destroyed.

The nineteenth century Yell scholar Laurence Williamson left copies of his letters to Mary Watson of Fetlar among his papers. He loved Fetlar greatly, and no doubt Mary too, but she wouldn’t marry him. Some correspondences are poignant because of what doesn’t happen. Laurence died single.

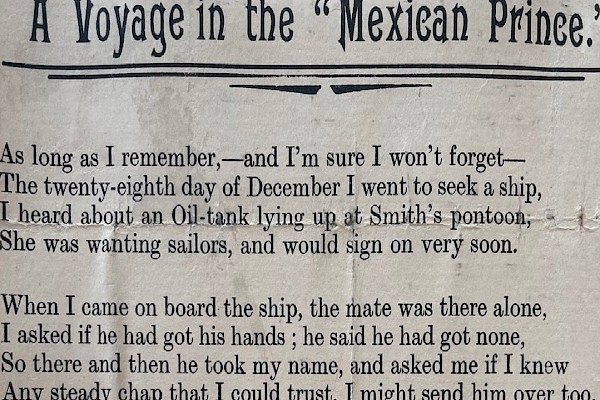

Robert Abernethy of Brouster and Thomasina Manson had a long correspondence, and courtship. Thomasina’s letters to Robert live on in the Brouster Papers (D39), starting around 1898. They married in 1909. There’s nothing fancy about the paper, perhaps a good sign, but it is good quality, folding up nicely into small envelopes about 120 by 95 mm. We don’t have Robert’s replies but it looks like they corresponded very regularly. Thomasina working as a clerkess in 1901. She had a good hand, wrote articulately, and spelled well. It’s tempting to think of the flicker of the peat fire flame over the page as she wrote, or the glow of a paraffin lamp.

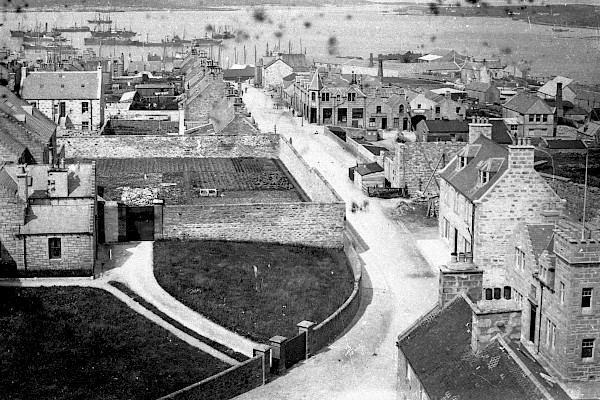

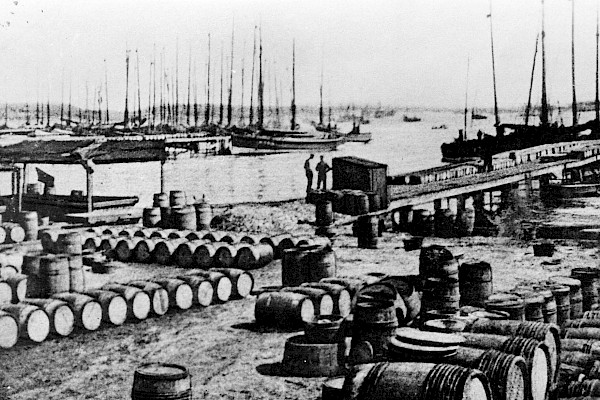

For people like Thomasina and Robert compulsory schooling had given them literacy skills to show how they felt. Being able to read newspapers, magazines, and books gave them models of how to express themselves. An efficient and cheap postal service helped a lot too, although they might just have given a letter to someone going the right way. In modern terms they weren’t that far apart, she lived in Foratwatt and he in Brouster, but it was a real distance in the days when people had long working hours and went about on foot. The weather sometimes intervened, and Thomasina does mention that she was glad Robert hadn’t visited her in a storm! A letter maintained a relationship.

You won’t forget your little sweetheart will you? But come and see me again. I should be so miserable if you didn’t love me.

These letters offer little insights into life and society. In one (D39/7/8/1/3) Thomasina apologises for not asking him inside on a Sunday night. Everybody else in the house was out and she was alone. Both were clearly anxious to observe propriety. Thomasina remarks on attending chapel twice in one day, so they probably considered issues like how the Lord wanted them to behave. There’s other issues too, like avoiding a few digs in the ribs or being the subject of public comment. In Shetland society the most dreadful punishment is – Folk’'ll spaek aboot dee.

Thomasina and Robert’s story does have a happy ending, since they married in 1909. They had a family, one son, born in 1913, but happily ever after didn’t happen. Thomasina died shortly after the birth, and Robert lived on until 1915. It must have been very hard on Robert. The letters suggest a devoted pair of people.

Transport and communications are so different now, far fewer people write letters. They don’t have to, its simply so much easier to see another person. Even if they are on the other side of the world couples can communicate face to face. Telephones are ubiquitous, not novel. The Brouster letters are from over 120 years ago. In 2143, will there be people sitting in archive searchrooms, going through collections of preserved text messages? They might be sitting quietly for a while, then asking, is this an emoji, what does it mean?