One Piece at a Time

From teapots to lepidoptera, there is a place for objects, large or small, in Shetland’s Museum and Archives’ collection. Here, archivist, Mark Smith explains the cultural significance of collecting such items.

When people visit the Shetland Museum and Archives, they only see a sample of the things we look after. The documents people read in the archives, or the objects peered at through carefully defingerprinted glass, are a bit like the slim selected works of a poet who has been writing books for fifty years – they are the glittering lures resting on the mirrory surface of the water which, occasionally, tempt visitors into places much deeper and less well-lit. A single sentence in a letter can be the jumping off point for a book about some adventurous Shetlander nobody has ever heard of; the glimpse of an object tossed casually in a midden thousands of years ago can open the door on a parallel world that existed in the place where we live and work every day.

The artefacts and papers folk see in the Museum and Archives are, in a sense, Shetland history’s Greatest Hits. But that compilation album – a pleasant listen for a few hours before a visit to the café for coffee and scones – is culled from a sizeable back catalogue housed in climate-controlled storerooms rarely visited by the public. Over the years we have gratefully received donations from hundreds of people – from single objects to large assemblages – and we are always interested to see the things people collect. Often, visitors are doubtful whether anyone will be interested in their great-aunt’s envelope of postcards or their emigrant second cousin’s penknife, but even the smallest object can add to our knowledge of the place the Museum and Archives was built to celebrate. Unfortunately we can’t display all the things we care for, but every object and paper in our collections contributes towards a better understanding of our archipelago’s past. The richer our collections become, the better able we are to tell Shetland’s story.

This all leads us towards the rather obvious point that, if it wasn’t for the human impulse to collect things, no matter how obscure or arcane, the Museum and Archives couldn’t exist. The institution thrives because, for reasons that even collectors themselves might not be able to explain, people have decided it might be a good idea to start keeping teapots or watches, letters or lepidoptera. The collections we look after at the Museum and Archives are the collective work of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people. Our holdings have built up, item by item, from archaeological discoveries to loft clearances, over many decades. The things on our shelves and in our cabinets are all part of a resource that has emerged from the community we serve. Staff spend much of their time cataloguing, cleaning and classifying these papers and objects, but none of this work could be done were it not for people who have spent many years hunting for the next addition to their collection . . . and the next, and the next, and the next.

Sometimes, though, collections can get out of hand. The impulse to gather can be too strong. The half-a-dozen carriage clocks, all chiming away pleasantly on the hour, can multiply and fill every room in the house, attracting frequent visits from neighbours complaining about the noise. Collectors, in other words, can occasionally tend towards the obsessive. Take, for example, the Collyer brothers, Homer and Langley, who, in the first half of last century, filled their house in New York with the most extraordinary collection of objects. When the brothers died in 1947, police and workmen took more than 100 tons of possessions from their home at 2078 Fifth Avenue. During their strange, reclusive lives, the brothers had collected, among other things, fourteen pianos, an X-ray machine, the folding top of a horse drawn carriage, over 25,000 books, a collection of guns, bowling balls, the jawbone of a horse, and the chassis of a Model T Ford. After the brothers passed away, parts of their collection were displayed at Hubert’s Dime Museum in Times Square. The exhibit included, rather gruesomely, the chair Homer Collyer was sitting in when he died.

The Collyers, of course, are an extreme example of collecting fever, but the idea of keeping things just because is, perhaps, something all collectors share. And, here at the Museum and Archives, we’re very glad they do. In the Archives, for instance, one of our most prized items is a huge scrapbook compiled by Lerwick draper E.S. Reid Tait. In the scrapbook, which is a good two-handed lift for an able-bodied archivist, there are hundreds of invitations, concert tickets, timetables, pieces of headed paper, membership cards, and many other kinds of ephemera. It is a collection of seemingly unimportant things that most people would have used to light the fire. Although Reid Tait wasn’t anywhere near the Homer and Langley level of collecting mania, Shetlanders can be glad he had a tiny dose of the bug. If he’d been free of it, then we wouldn’t have his scrapbook and the rest of the large collection of papers and objects he gathered together. But, because he was afflicted (albeit mildly, compared to Homer and Langley), we know a great deal more about Shetland than we might have done otherwise.

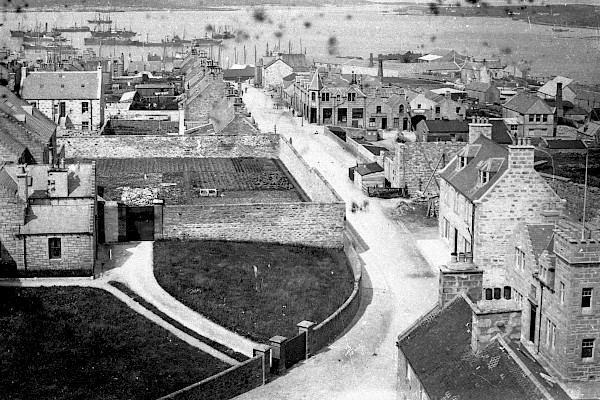

But if collectors run the risk of being overwhelmed by the things they collect, there is usually a complementary impulse towards keeping things under control. In a fabulous essay about unpacking his library, the German author Walter Benjamin (himself a sufferer of the sub-genus of collecting fever bibliophilia, or book collecting), writes ‘there is in the life of a collector a dialectical tension between the poles of disorder and order’. In other words, most collectors, as a corrective to the diffuse and self-propagating practice of acquiring more and more things, come up with some way of organising the objects they own. Collectors work hard to avoid chaos. They, as do curators and archivists, spend many years sorting and cataloguing the various objects the past has handed down. They come up with taxonomies and systems of categorisation; with boxes of neatly written index cards and spreadsheets; numbering systems and databases. As part of the archives catalogue, for example, there is a detailed listing of papers from the Sheriff Court of Shetland. This list allows people to search the details of over 31,000 records produced by the court during the last five centuries. If somebody’s ancestor was accused of stealing sheep, or, as happened in 1818, they spent Christmas day walking around Lerwick drunk, naked and waving a sword, then the listing of the Sheriff Court papers held in the archives can lead them towards the details. In many cases, the only mention of events will be in these papers. If a catalogue had not been produced, then the stories the papers tell would remain locked inside a box, unlikely to ever be seen.

Here at the Museum and Archives we are proud of the collections we care for. We are always keen, though, to add to them, so if you have anything you might like to donate, please get in touch and we’ll be glad to have a look (as soon as our doors are open again!). We can’t promise to accept every donation, but new discoveries are one of the most exciting things about working here. On mantelpieces and in cupboards all over Shetland, there may be objects that folk hardly even notice, but it is often the most undistinguished, apparently throwaway thing that gives us the next piece in the jigsaw puzzle of our islands’ past. And that puzzle, I’m happy to say, is one that will never be complete.

This article first appeared in 60 North magazine, Issue 22/23, published by Shetland Amenity Trust.