Talking Toevakuddis

Hazel Hughson, Barbara Ridland and Joan Fraser explored the use of cloth to pay taxes in a series of thought-provoking art forms in their recent Gadderie exhibition, inspiring us to consider why and how cloth was fulled in the sea and the hard work and dangers faced whilst producing this essential commodity. Many visitors to the exhibition were intrigued by the title and subject of the artists’ work – the word toevakuddi being as unfamiliar as the processes involved.

Unlike other cultures where fulling was done by pounding with hands or feet or mechanically in a mill, in Shetland this took place at the shore. The cloth was stretched out and secured to the rocks and the motion of the sea and rocky surfaces agitated, strengthened and thickened the fibres. Such places were called toevakuddis or teevakuddas, a name rooted in the Old Norse þœfa: to full and koddi, kodda: a roundish rock, roundish depression or pillow. There are different types of toevakuddi – firstly a deep cleft with smooth bedrock and constant motion of the sea, which sometimes has an inner pool or bowl hence the kuddi/kudda name. Others are shallower clefts with a pillow like form of bedrock, which becomes dry at low tide and the motion of the sea is gentle. In Faroe fulling also took place at the shore, but instead of a þœfa name, the place names include the element váð.

One of the few written accounts was by Patrick Menteith in 1684. He wrote:

“there are no Walke Milns here, that is done either by their hands and feet, or by the Sea, called Tuvacuthoes. Thus in a place betwixt Rock and the land, through which the sea Ebbeth and floweth, they fasten a Web of Cloth, the one end upon the rock, and the other upon the Land, and the Sea by its motion to and fro Walkes the Cloth very thick; which cloth they call Yelt or Wadmeal”.

I had never heard the word until I joined Shetland Amenity Trust over 20 years ago and a conversation with my colleague, curator Carol Christiansen, made me realise the significance of these places, often only identified through the survival of the place-name, which included elements like taava, teifa, teeva, toeva, toova, dova, duffa, kudda and kuddi. Although I knew about folk paying their rent in butter, oil and wadmal, the word toevakuddi was new to me and led to my quest to locate these places.

My starting point was Faroese scholar Jakob Jakobsen who recorded Shetland words and place-names in the 1890s. Jakobsen records Tøfakoddi and Tefakoddi in Cunningsburgh, Tøvakoddi at Ennisfirth in Northmavine and Colvidale, Unst, Tevakodda at Quarff, Bressay, Vidlin and Nibon, Devakoddi at Gletness and Tøvakoddis at Cullivoe.

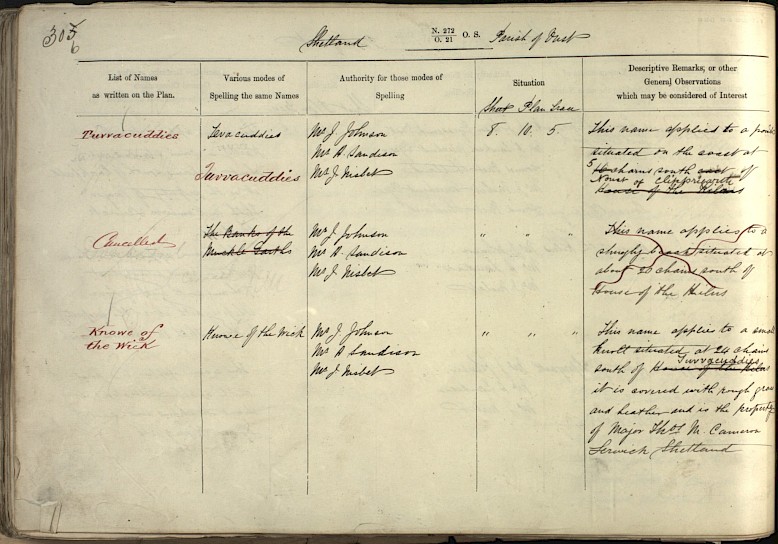

A few names were recorded as part of the Ordnance Survey (OS) in 1878 and appear on their maps in various forms. Toovacudda, Colvadale, Unst, appears on the maps as Tuvvaquida, but is also recorded as Tavacudda in the OS name books, and Tieffacudda at Helliness, Cunningsburgh, is recorded by the OS as Tara Cudda, but provides enough of a pointer if we didn’t have the knowledge of local folk to give the correct name and location. It has been difficult to identify where cloth could have been fulled at Tuvvacuddies at Uyeasound, but closer examination of the OS name books shows two different descriptions of the location, so a follow up visit is now necessary.

By far the best source of information was a range of archive sources and talking to history groups and individuals throughout the isles. This confirmed current pronunciation and variations from the early records, and revealed several more names including, perhaps most interestingly, the Wadmal Hol at Brecon and a few Washing Holes in Whalsay. We also confirmed the location of some of those recorded by Jakobsen, including those at Cunningsburgh, Gletness and Quarff.

The artists’ exhibition and associated talks by them and Carol Christiansen about her research and trials into the process of fulling using toevacuddis, has led to the confirmation of some more locations, including one in West Burrafirth. Da Yard o Toevakuddi near the rocky shore points to another toevakuddi, so we hope to visit this soon to try and identify the place where cloth was fulled.

Three projects recording the place-names, exploring how toevakuddis were used, and interpreting the process and significance of these places through art forms confirm the importance of place-names and oral information to inform research and an understanding aspects of our heritage and culture. In the same way as place-names are direct signposts to where brochs were located and sea eagles once nested, without the preservation of the name or local knowledge, we would only know about toevakuddis from a very few written accounts and would not be able to locate these places, once so significant to the daily lives of our forebears. If you have any information about a toevakuddi near you, particularly those at Brough in Cullivoe, Vidlin and Bressay, please contact placenames@shetlandamenity.org