The adventures of Ninian Neven

Archivist Brian Smith delves into the incredible story of his ten-times great grandfather the accomplished and unruly Ninian Neven. From Scousburgh to Yell and Edinburgh to Amsterdam, it is an incredible tale with endless twists and turns - fraud, adultery, illegitimate children, treasure, hooligans and even shots fired.

Readers who plod through John Ballantyne’s big Shetland Documents 1612-1637 will find hundreds of references there to Ninian Neven, my ten-times great-grandfather.

He was born at Scousburgh around 1586, the son of a small laird and official. He and some of his brothers became notaries public, and thus became involved in the transmission of property all over Shetland. Ninian’s handwriting was small and very neat, perhaps belying his wayward character and career.

He married Osla Edmistoun, daughter of the minister of Yell, and made his home at Kirkabister there. As time went on he broadened his interests. He had business relationships that we know little about. He got a lease of church taxes in Yell and Fetlar. In the early 1620s became clerk to Robert Finlason, Shetland’s brutal sheriff depute.

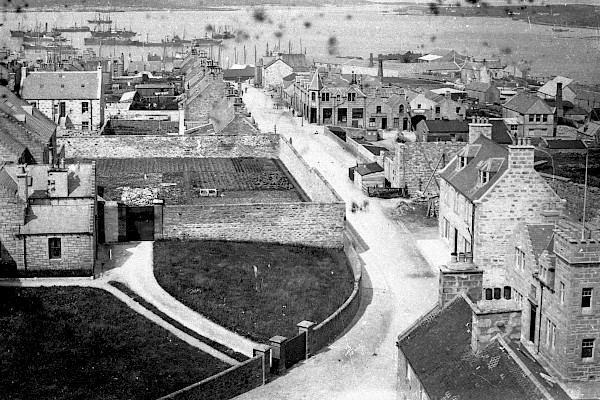

Mike Pennington's excellent pic of North Sandwick in Yell, where Ninian Neven lived. Ninian's house was probably on the site of the house in the pic.

https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/687595

He became embroiled in disputes, sometimes violent, with landowners and relatives. He acquired the large township of Windhouse in Mid Yell, apparently by fraud, and went to live there. Eventually the Scots Privy Council took an interest in what was going on in Shetland, and Ninian was imprisoned in the tolbooth of Edinburgh. I needn’t rehearse these events here, because they feature at length in Ballantyne’s book. It’s enough to say that Ninian got away with it, because there were huge faults on all sides.

Windhouse from Mid Yell Voe, Brian Smith

He went back to the notarial work that engrossed him all his life. Eventually he became chamberlain in Shetland for the earl of Morton. But his career was punctuated with strife from time to time, and explosions – literally, in June 1638, when he and a relative were nearly blown to pieces in Edinburgh.

Osla Edmistoun died in December 1646. Ninian was by then sixty. They had six children; the eldest, Gilbert, had his father’s unruly habits. By that time Ninian was living at Sandwick in North Yell, and Gilbert at Windhouse. Ninian also had a pied-a-terre at Gremista, near Lerwick.

They were well-off. On the three townships, large working farms, they had 19 plough-oxen, eight young oxen, 23 horses and mares, 28 cows, five young heifers, 11 year-old bullocks, and 240 ewes and sheep. There were 240 thrave of bere and oats in the barns. They had an eight-oared boat, two sixerns and three fourerns.

Ninian got married again, almost immediately, to Marie Gifford of Waddersta. He also fell in love. One day in the summer of 1650 he arrived in Yell with Jean Sinclair. I can’t be certain who she was, but I suspect she was the sister of Laurence Sinclair, a merchant in Lerwick who was or became an official in the town.

They headed for the business premises of Kurt Warnekin, a German merchant in Cullivoe, and had a drink there. Then Ninian sent to Sandwick for his best horse. Jean had business at Gloup and elsewhere in Yell. Her brother William, another merchant, had sold some salt to somebody there, and Jean had come to Yell to pick up the money.

Ninian now took her on his horse to Gloup. She sat behind him as he ‘horsed’ her: that is the verb used in the documents. On the way they called at Andrew Henryson’s house in Cullivoe, and Ninian spoke to Andrew’s wife.

‘Margaret,’ he said, ‘here is a stranger come to get some moneys from your goodman that he was owing to her brother. You shall do well to provide her and me with supper and good cheer when she comes back. We shall be beside you for a night.’

‘Sir,’ replied Margaret, ‘what gentlewoman is that, that you have so great a care for? I never saw you horse your own wife that way.’

‘She is a stranger,’ said Ninian, ‘and we ought to be kind to strangers.’

This little exchange tells us a lot about Ninian and his neighbours. On the one hand he speaks peremptorily to Margaret, demanding lodgings for the night; on the other, she gives as good as she gets.

When they got back to Cullivoe, he left Jean with Margaret, and headed back to Kurt’s booth to drink. Jean went to bed in the ‘hall’ of the house, another woman with her. When Ninian came back, eventually, he slept in a barn with his son James, who happened to be there. They were observing proprieties.

In the morning they took a boat to Ninian’s house at Sandwick. He asked a servant to bring them a ‘kit’ of milk, and he took a sugar loaf from a kist. He put it in the milk, and gave it to Jean to sup. His wife doesn’t seem to have been there, but she heard about the incident later. She was angry: ‘He was never so kind to me,’ she complained. In due course she went to Cullivoe to check how close the barn where Ninian slept was to Jean’s bed in the ‘hall’.

The events became notorious. The church began to take an interest in them. As the earl of Morton’s representative in Shetland, Ninian had been partly responsible for installing William Reid as minister of Unst. Following the events at Cullivoe they fell out.

Sometime at the end of 1648 they met in Baltasound, and after ‘many reproachful words’ Ninian beat the minister with a stick. And a few months later Gilbert Neven was in Uyeasound, looking for otters to kill. The minister came along, and Gilbert assailed him with his otter baton. Ninian was nearby, and he intervened. He was ‘very wroth’. Perhaps by this time he realised that things were getting out of hand.

But that didn’t make him relent. In May 1649 he was summoned to the kirk of Baliasta to explain himself. The explanations were succinct. He confessed that he had struck William Reid with a stick. He admitted that he had called him a false knave, a ‘fool fellow’ and a cheat. He said that Reid was a debauchee, and that, although he (Ninian) had brought him to Shetland, he would help to send him back again in shame and disgrace.

The ministers present weren’t very taken with his behaviour. ‘He came in in a boasting manner’, they reported, and said that if they didn’t accept his account of the affair, ‘he should hereafter challenge them as perjured men’, and ask the earl of Morton to intervene.

These events took place amidst cataclysmic ones in the nation. In December 1648 Colonel Thomas Pride had purged the Long Parliament in London, leaving a residue, the Rump, who were willing to try the king for treason. The following month Charles I lost his head, and a Commonwealth was proclaimed in England.

Eventually the new radical regime came to Scotland, and in Shetland, as we shall see, Ninian became part of it. In the meantime, however, his life had become more complicated. Jean Sinclair was pregnant. As he always did, Ninian acted with energy. He sent her to Holland to have the child, in the hope that it could be concealed, and arranged to pay for its upkeep.

Concealment wasn’t feasible in a place like Shetland. In November 1650 William Reid raised the matter at the presbytery. The following August the brethren considered the matter. They had a witness, Marion Thomasdaughter, who told them that five weeks after her arrival in Holland, Jean had had a daughter in Haarlem. The child was baptised Elizabeth, and Jean had told the authorities that her own name was Jane Kier, and that the child’s father’s name was Jacob. She left the child with a fostermother in Amsterdam, and came home.

She was ill. The presbytery went on pursuing her. They consulted her brother Laurence, who had written a letter to her while she was in Holland. They spoke to another witness, Margaret Nicolson, who had been in Holland – perhaps as her friend? - and had spoken to the fostermother.

In April 1652 the minister of Tingwall visited Jean, on her sickbed. She denied that she had had a child.

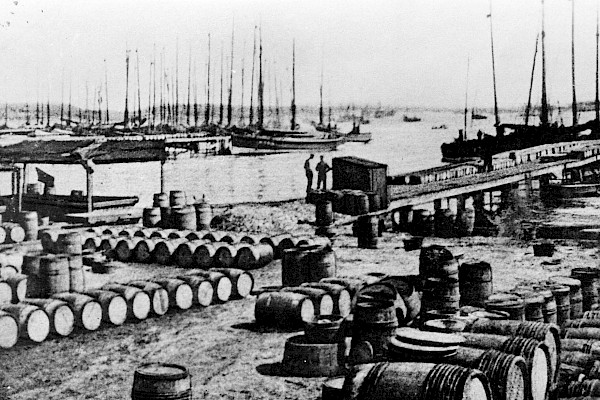

Ninian seems to have washed his hands of the affair. While the minister was visiting Jean, Shetland’s gentlemen were acknowledging the new Commonwealth, and Ninian became a stalwart supporter of it. But he had other problems in the offing. In March 1653 a Dutch Eastindiaman ship, the Lastdrager, stuck on a rock at Crussaness at Cullivoe. Ninian, who could speak Dutch, took charge of them, and also of chests of silver which had been on board.

The silver attracted the attention of James Keith of Benholm, a servant of the earl of Morton. He assembled a band of hooligans and provided them with ‘bellicall furniture’ (weapons), as the documents put it. They headed for Yell, and on 29 March they arrived at Sandwick. One of them gave Ninian ‘a great blow in the hinder head’, and another shot his daughter Bathsheba in the side. They took over the house, tied up Ninian, and looked for alcohol to drink. From the cellar they removed a barrel of ale and half a barrel of Spanish sack.

They drank toasts to Ninian ‘Rumples’, as they called the supporter of the Rump parliament, and - another nickname they had for him - ‘Parliamentar’.

Eventually they took him to Scalloway, and locked him up in the castle. He remained there until the end of May, when General Monck, at that point the main military commander of the Commonwealth, arrived in Bressay Sound. Monck immediately freed the prisoner.

And what of Jean Sinclair? The following month the minister of Tingwall went to see her again, accompanied by two of his elders. This time she was frank. She confessed that she had had a child in Holland, and that Ninian Neven was the father of it. ‘She acknowledged that the Lord had never prospered anything she put her hand to since she had so long concealed the same.’ Soon afterwards she died. It’s a sad story.

The Lastdrager events, and other alleged faults by Ninian and his son - including his adultery with Jean - were being discussed in the Commonwealth courts. Bathsheba Neven travelled to Bressay Sound to complain to Monck about the wound that she had received. She died not long afterwards. Her mother, meanwhile, was still seething about Ninian’s romance with Jean. She drafted a complaint against him to one of the Commonwealth officials, but her father talked her out of it.

William Reid had his own complaints to make; but nothing came of them. Eventually he transferred to the parish of Durris in Aberdeenshire, ‘because he could not get justice nor redress … and for fear of his life’.

Ninian Neven died around 1663: we don’t know the exact date. His adventures show that he was an accomplished man, and an unruly one. I don’t think that Jean Sinclair benefited from her friendship with him.

I am grateful to John Ballantyne for help.

Brian Smith, Archivist, June 2020

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog. We rely on the generous support of our funders and supporters to continue our work on behalf of Shetland. Everything we do is about caring for Shetland's outstanding natural and cultural heritage on behalf of the community and for future generations. Donations are welcomed and are essential to our work.