The Man Behind the Lowrie Stories

Sometime in the 1920s a middle-aged businessman in Lerwick began to write stories. He didn’t write about his native town. The hero of his pieces was an archetypal rural Shetlander, Lowrie, whose surname is a bit of a mystery.

Joseph Gray shared his work with friends and relatives, and they shared it too. The Lowrie stories became hugely popular, and in 1933 they appeared in book form. Lowrie was a best-seller. A second edition appeared in 1934, the year that Gray died.

The Lowrie stories are written in the densest possible Shetland dialect. It may seem strange that someone born in Lerwick, who lived there his whole life could write fluently in that rural patois.

But Gray had predecessors. Peter Greig Work, author of stories called Fireside Cracks, published between 1897-1904, and Thomas Manson, who wrote Humours of a Peat Commission in 1918-24, were also Lerwick boys. They too wrote accomplished dialect tales. Greig, Manson and Gray, Lerwegians though they were, had strong family connections with Shetland’s countryside and its language and stories.

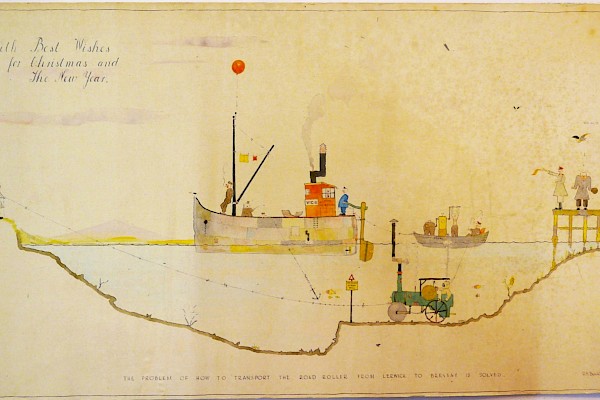

Sometimes critics have heaped ridicule on Lowrie. They say that it is hopelessly out of date, the work of someone ignorant about the modern world. The problem with that theory is that Joseph Gray was a pioneer motor engineer in Shetland. He was at the very forefront of modern developments here, at the moment when Shetland’s herring fishery was booming.

He became agent for crude oil engines, and he and his employees fitted them in Shetland boats. He established a large general blacksmith business. When motor cars arrived here he built Shetland’s first garage. During the First World the army and naval authorities employed him to maintain and repair vessels and vehicles. The author of Lowrie knew all about the modern world.

Lowrie is a Shetland classic. As well as the original editions there were successors in 1949 and 1991. It is not a ‘kailyard’ work, sentimental in the way that Shetland and Scottish stories often are. Peter Greig’s Fireside Cracks, for instance, is sentimental in the extreme.

There is wild humour about Lowrie’s adventures. In his first story, famously, he and his wife ‘wrastle’ with a new hen. He buys a Ford car and a wireless – chaos ensues – and his trips away from Shetland end in disorder. So does his visit to the picture house. Even posting a parcel in Lerwick becomes nightmarish. Every now and again he meets an academic, official or clerical visitor. They utterly fail to understand each other. Their mutual misapprehensions are hilarious.

On a glorious occasion Lowrie and his comrade Olie visit the Hillswick Hotel, an episode dramatized a few years ago by Ewen and Stuart Balfour. They hover over the menu with a pen. They think that hors d’oeuvres is horse livers. ‘Loard bliss me,’ Lowrie remarks, ‘dir not pitten yon for human maet. Dats waur is kannibals. Pit doo nae mark dere.’

Lowrie is a difficult work for a modern audience. Gray’s Shetland dialect can be nearly impenetrable, and he supplies no glossary. His spelling is eccentric. In an era when some readers can’t master more than 280 characters, or read more than a paragraph or two, his slabs of text may pose problems.

But it’s worth persevering. Lowrie opens a window on to a Shetland scene that was disappearing in the thirties and in 2021 has gone for ever. Joseph Gray portrayed Shetlanders and others trying to come to grips with modern society, and sometimes failing. Their misanters and disasters are hilarious.