Shetland's jubilations (Part 2)

1977 Silver Jubilee

Elizabeth II reached her Silver Jubilee in 1977, and Shetlanders threw themselves into the excitement, with the usual parties and bonfires. At Fair Isle there were children’s games, a fancy dress parade, and a dance in the hall. The Sumburgh airport held an open day, and there were gala days at the Walls and Brae Schools. All wasn’t smooth in town alas, and although the Shetland Times observed “Lerwegians seem to be immune to Jubilee fever”, the chairman of the town’s gala committee declared “we cannot stress our feelings strongly enough at the apathy and non-events to celebrate the Queen’s silver jubilee”. The context was the oil boom, and Council coffers were stuffed, so the target was the S.I.C. Leisure & Recreation Department, and the event committee questioned why the Department hadn’t organised and supported a town event. This was the beginning of the “why doesn’t the council organise this?” mindset, perhaps.

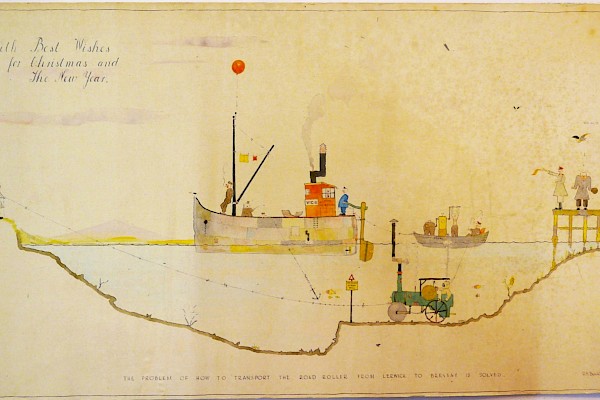

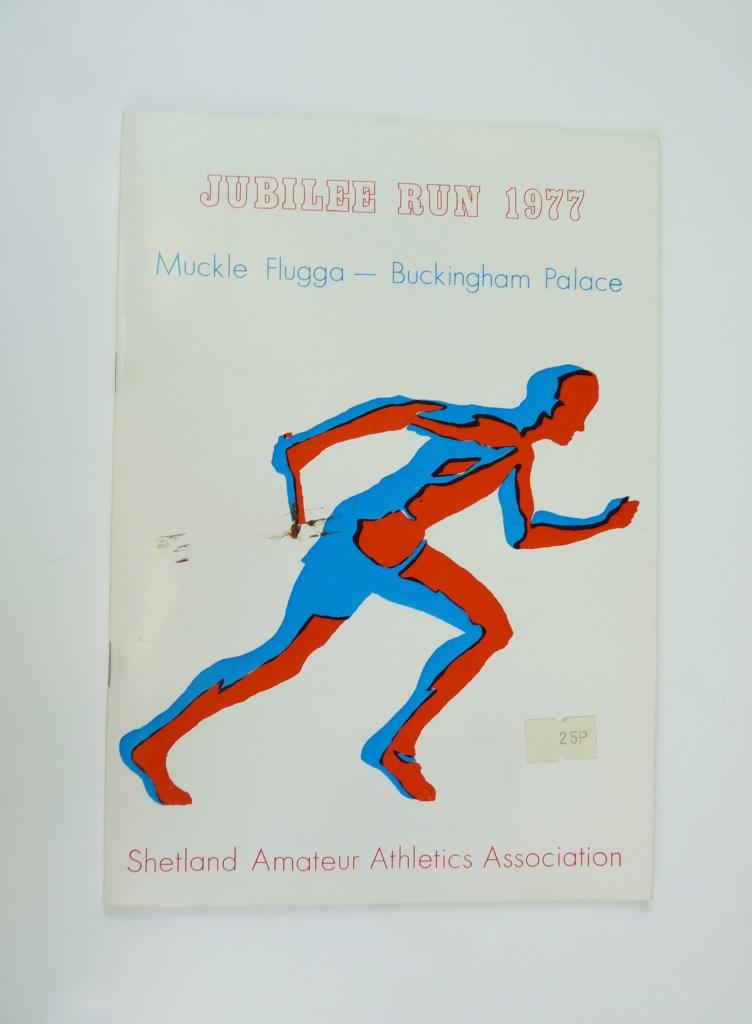

The lack of official commemoration contrasted with the local event that captured the imagination – the Shetland Amateur Athletics Association’s relay race from Unst to Buckingham Palace. Perhaps from a sense of guilt from the criticism over the lack of official celebration, the Council now co-opted the glory, and provided a civic send-off for the S.A.A.A.’s initiative. There’d been official indifference but now Leisure & Recreation provided help and “there had been tremendous enthusiasm from organisations and civic dignitaries in cities and districts through which the message would be carried”.

2002 Golden Jubilee

This contrasted to the previous gold edition. Now, it was far more about fun for young and old, with a Royal aspect added-on. As ever, the schools made fun days for their pupils, such as at Scalloway, where there were games, homebakes, and a quiz, and at Scalloway and Sandwick where each pupil got a souvenir medal. Galas had become part of the Jubilee format, like one at Weisdale – with everything from gladiators to pillow fights – or at Sandsting, with a carnival of decorated floats and a dance in the Skeld hall. More than most places, Unst knows how to put on a doo, and it was what the Shetland Times called “the most lavish affair”; a weekend programme of events, football, cricket (R.A.F. Saxavord versus Unst Select), a family day at the leisure centre, a ball. The local brewery made a commemorative Jubilee ale, and there was a live broadcast from Sky TV.

2012 Diamond Jubilee

Last time round, the components were familiar again. At Burra, church bells rang and folk tucked into teas at the hall; there was a garden party at Hillswick; a hall banquet at Gruting. Schools again took the lead, such as at Brae, where pupils wrote poetry, composed a Jubilee tune, and planted a Jubilee tree. And beacons were favourites once more, with over 200 folk attending the one at Saxavord, Unst, alone. Also in Unst, the Deputy Lord Lieutenant hoisted the Union flag, children and adults singing the National Anthem, in a way that’d be familiar to those at the 1897 Diamond Jubilee.

Gradual changes to Jubilees reflect how society does, and there were new trends. Shetlanders mimicked the street party motif which doesn’t quite fit our rural setting, but they were a great success; 300 people attended the Baltasound one and 150 at Mid Yell. Jubilees are usually set in life today, but nostalgia was now part of it, where people at the Burra tea party donned 1950s costume, and at Scalloway School pupils heard a vintage broadcast by the then Princess Elizabeth.

Go to blazes

The (literal) highlight of a Jubilee is the beacon. There are scores of bonfires each time, and the biggest of them is the beacon – a fire on top of a prominent hill, from where another beacon can be seen, and so in turn the length of Shetland. Margaret Chalmers, in 1809 Verses on the Jubilee night, at Lerwick, hoped that “with tapers and rockets, and bonfires around, I’m sure we were doing our best”.

The efforts folk went to in Northmavine in 1887 are impressive anyone. People decided to celebrate with a bonfire on Ronas Hill, and the Shetland News observed “the work was no easy matter, as all the material required [had] to be transported by human strength from the foot of the hill to the top”. Folk carted wood from Hillswick to Heylor, where they crossed Ronasvoe by boats, ready to begin their uphill plod; “each one takes a bundle on his back and commences to scramble up the steep and rugged side… for the first three or four hundred yards the path is very steep and difficult, and we find it necessary to stop and take breath”. Sixty people went to the summit, where they built their beacon. There were rockets, drams, and a dance, rounded-off by singing the National Anthem, toasting the queen, and cheers all round. They must have been puffed-out by the time they finished at 1.00 in the morning, but they then had to begin their weary way back!

For the 1897 Jubilee there were bonfires again, and Hay Shennan, recorded that “never had they been so numerous as on this occasion”. He went to the beacon on the Wart, Bressay, and from there folk could see sixteen other fires through Shetland. Folk gathered at the Wart shoved kettles into the bonfire to brew-up festive tea. For the 1977 Jubilee there were the usual “unofficial” bonfires, plus four official beacons that were part of the chain that ran the length of the kingdom. These were: the Wart, Fair Isle; Erne’s Ward, Dunrossness; the Wart, Bressay; Saxavord, Unst. Clearly, Fair Isle’s role was the most important link in the chain in whole country, otherwise the whole scheme would fail! The beacon at Dunrossness was lit by the Lord Lieutenant, attended by around 250 folk.

A good day for it

Finally, what nobody can plan – the weather. Because Jubilees generally take place in June (1809’s was in October, and 1935’s in May), conditions have generally been kind. Margaret Chalmers described the rockets and fires in the moonlight at Lerwick in 1809; “when illuminations take place in the absence of the moon, the sea reflects the lights. On the happy evening here referred to, the moon being at the full, prevented the effect of the liquid mirror, but made ample amends by the pleasure which the sight of that beautiful luminary, holding her way through an unclouded sky, afforded.” In 1887 the day was crowned by good weather for the parades, picnics, and games, and in Lerwick, Thomas Manson reminisced that “the sun shone gloriously all day. Not a drop of rain fell; the sky was clear, and the sea smooth; better elemental conditions could not have been wished for.” Meanwhile, in Northmavine, “as the day wore on the dark heavy clouds began to disperse, and the sun shone out in all his glory”.

Of course, we can’t be certain things will go pleasurably, and some Jubilees haven’t been summery at all, depending on where you were. For the 1977 Jubilee at Unst “160 children stuck it out for most of Tuesday afternoon despite a cold blustery wind”, and when on 2002 Jubilee the Whalsay Church had a sandcastle competition, the teams building them maybe had the benefit of damp to stick the sand together, for the Shetland Times described conditions as “poor”! During the 2012 Jubilee things went better weather-wise, and anyone viewing the telly could see London was gloomy whilst Shetland was bright, and a Shetland Times correspondent thought “the Queen and Prince Philip might have done better to forsake the River Thames for the Pool of Virkie on Sunday – it was much brighter and very much drier”.

A Platinum Jubilee is unique – we’ve not waited 70 years for one, but a thousand – so please let it be sunny and minus midges!

This article was first published in the Shetland Times.